Andrea Bocelli,

My Christmas / Mi Navidad (Verve, 2009; re-release re-mastered, 2015). David Foster, producer and arranger; William Ross, arranger. Link on

Amazon;

Barnes & Noble;

Verve. I was introduced to this five years ago (December 2013), when we took a weekend vacation on Siesta Key, near Sarasota, and ate dinner at City Pizza Bar and Italian Grill. The endings caught my attention, I asked the waiter, and he replied that this recording was the owner's seasonal favorite.

Disc list: 15 tracks. The eight upper-register endings are indicated with an asterisk (*).

*1. "White Christmas"/"Bianco Natale." A line goes down, as in the original melody, in the first verse. Bocelli then turns it upward in the closing cadence -- and holds the final ^8 cleanly for a nearly impossible length of time.

*2. "Angels We Have Heard On High." Two halves: straightforward presentation by him, then choir enters -- two (or three?) half-step key slides -- he joins and completes with the same closing figure: essentially ^5-^8 leap with quick ^6 & ^7 -- but these are clearly articulated; it's not a gliss.

*3. "Santa Claus Is Coming To Town." With children's chorus. At one point he sings a descant to their melody. Later it's reversed. Twice he closes by lifting ^2-^1 to ^9-^8.

*4. "The Christmas Song" with Nathalie Cole. He's doing Sinatra/Crosby in this one. So is the arranger (slow 1950s? ballad style and chord changes). He lifts the final notes up to ^8-^9-^8. He even goes a third higher in the coda.

5. "The Lord's Prayer" - with The Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Sounds like you would expect it to.

6. "What Child Is This" - with Mary J. Blige. Gospel-tinged soprano. They go back and forth. She seems too constrained by the arrangement to be convincing. The Italian band interlude doesn't help.

7. "Adeste Fidelis." With full orchestra and trumpets and timpani, and a somewhat subdued chorus; sounds like a Baroque/high Classical orchestra. He substitutes a prolonged ^5 for ^2 in the final cadence.

8. "O Tannenbaum." Pastoral setting with drones, later a flute solo, guitar, four horns. He sings in three languages. No rising line or leaping figure at the end.

*9. "Jingle Bells" - featuring The Muppets. Obvious but still funny opposition of a (too) slow lyrical tenor and the upbeat Muppets (he joins them). Simple inversion of melodic direction in the cadence:

*10. "Silent Night." Children (?) in intro, wordless -- most movie-music-like sound on the album. They reappear between verses and at the end. After a deceptive cadence (vi rather than I on the final chord), he repeats the phrase and goes up in a leisurely ^6-^7-^8. One of the easiest to manage in terms of voice leading -- same as in "Jingle Bells":

11. "Blue Christmas" - with Reba McIntire. Similar to "The Christmas Song" but without the '40s-'50s tones.

12. "Cantique De Noel." Consistent sound of a tenor aria throughout. Even a little ornament on the final dominant.

13. "Caro Gesu Bambino." Perhaps simplest of the lot; song, not aria. Relatively low tessitura for him; almost baritone sound.

*14. "I Believe" - with Katherine Jenkins. Very movie-ish duet, mostly string orchestra behind. A key shift halfway through. At the end she is on ^3, he is on ^5, then leaps cleanly up to ^8.

*15. "God Bless Us Everyone." Full-throated version of a song from Disney,

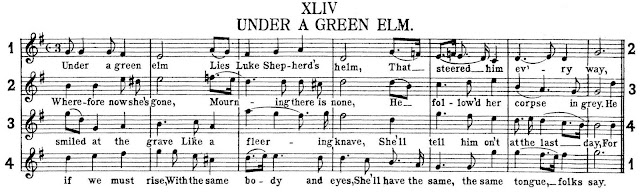

A Christmas Carol, by Alan Silvestri and Glen Ballard. The tune itself ends in the upper register (see this page:

link; click on the "piano" image for a readable view of a full verse). At the end (coda): he manages to overtop with a ^10-^9-^8. Here is the beginning of the song (a clear fifth frame is boxed) and the verse ending in the upper octave: