Compositions using the ascending line in the minor key are very few indeed, but they include one of the most powerful examples of the rising line and three-part Ursatz in the entire repertoire of traditional tonality: Francois Couperin’s masterful Passacaille (en rondeau), from the Pièces de claveçin, 8e ordre. The rondeau, whose reprises alternate with a total of eight couplets, consists of two statements of a phrase that seems to offer no counterbalance to its ascending Urlinie: all parts including the bass are swept upward to the cadence. Even the ornamentation contributes, with the arpeggios of measures 2-3. There is a subtle opposing force, however, in a structural alto that descends from ^5. On the scale of the whole Passacaille, the reiterations of the rondeau result in a combination of grandeur and bleak inexorability that certainly justifies the high praise many commentators have given this composition.

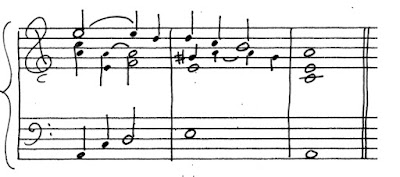

Here is the rondeau theme:

And here is an annotated version of the lower part of my Example 12 from the JMT article. "Overlap" was the term Allen Forte used for one instance of what is more commonly called "reaching-over" (Schenker's Übergreifen). A line can be generated by means of a series of overlaps, as here.

And here is an annotated version of the lower part of my Example 12 from the JMT article. "Overlap" was the term Allen Forte used for one instance of what is more commonly called "reaching-over" (Schenker's Übergreifen). A line can be generated by means of a series of overlaps, as here.

Figure g is reproduced in (a) below. The root movements underlying Couperin's actual bass are aligned with (a) in (b). At (c), figure g is transposed to B minor and shown as the basic progression of the rondeau theme; at (d) the cadential 6/4 and the inner voice from ^5 (see my Example 12 again) are added.

The couplets in a French baroque rondeau cover the range of possible relations to the rondeau theme, with respect to motivic design and other textural and expressive features. In some rondeaux, the couplets are so closely integrated with the theme that the pieces sound like Italian binary-form movements. In many others, variety seems to be the priority: the first couplet might sound like the opening of a B-section and the return of the rondeau theme, therefore, like the reprise in a small ternary form, but then the second couplet might be quite different, etc. In the B-minor passacaille, variety of texture and figure definitely seems to be a high priority, along with descending movements that counter-balance the powerful figures of the theme. All this is obvious in the incipits of the couplets: