Yust does mention my article on proto-backgrounds (2009). As I noted above, he belongs among the "rationalizers" of Schenkerian theory (and so do I--in Neumeyer 2009, at least); he summarizes the earlier history very well (in paragraphs 0.1.1 & 0.1.2, and introductory paragraphs to subsequent sections). Although I can hardly claim to have offered a formalized theory in Neumeyer 2009, I did focus on a generative model (that is, building out from the background through transformations), which Yust also favors. Here is a sample, his Example 15; I have removed its analysis of the bass to show only the reading of the treble parts. The specific aim of the work is to portray contrapuntal melody (2 or more part-writing "voices") in a single diagram or figure (which presumably can then be subject to computerized comparisons). Level 0 is the "chord of nature" and is indistinguishable from one of my proto-backgrounds. At Level 1 the passing tone C is represented as a digression from the interval; then a second voice appears--as a hierarchically subordinate voice it is shown below the primary voice. Level 2, so to speak, harmonizes the two voices, drawing them together into a single diagram. The only comparison I can possibly make is to say that, in my view, Level 0 could just as easily have had the fourth F5-Bb5 instead of the third Bb4-D5.

In the details of his analysis, Yust brings out motivic thirds, beginning with the pick-up gesture. In my view, the fourth is more prominent, tying together accented notes at the beginning, F4-Bb4, and then being repeated. Stretched to a fifth -- one can hear the stretching in Enat5 -- the fourth can still be heard as a shadow within the compressed thirds that follow and continue throughout the continuation phrase. This theme, incidentally, is in the antecedent + continuation design, which Caplin regards as a hybrid but which I have found to be fundamental to 18th century galant style and have re-named the "galant theme" (link).

A reading using proto-backgrounds is not kind to my JMT analysis of the theme as using the registral variant, ^5-^6-(reg.) ^7-^8, since the stable interval would strongly imply/imagine ^5 (as F5) at the end. See below.

Thinking of the proto-background more abstractly, the initial fourth could be recovered -- circled notes below -- but the registral variant of the Urlinie would be undercut by this version, as well.

I still do think that a registral variant (link) is not difficult to hear in this theme and in the reprise (below), but it is obviously not compatible with a reading based on proto-backgrounds, which are after all biased in favor of registral definition and stability.

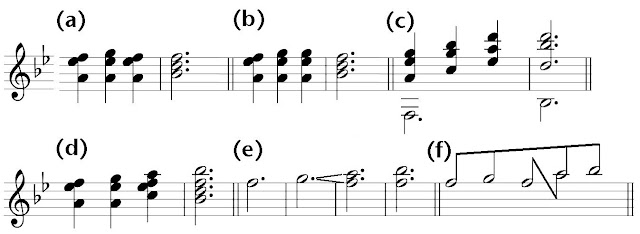

Note on the note: "Neumeyer (1987) . . . considers G to be an ascending passing tone rather than an upper neighbor. According to his interpretation, the G and A at the end of m. 7 are successive notes in a single voice, even though they both are sustained as part of the dominant ninth harmony over all of mm. 5–7" (Yust 2015, n33). I have written about the "waltz ninth" many times by now--here's a (link) to a recent post in this JMT series. Yust's criticism is the same as the one I've just made with respect to proto-backgrounds and does tend to undermine the registral variant. The waltz ninth is another matter. Nineteenth-century practice is broader--more creative and expressive--than eighteenth-century proscriptions. At (a), the ninth as neighbor note; at (b), the directly resolving ninth, a cliché in the waltz repertoire by no later than 1830. Note that the essential Schenkerian melodic note, C, is nowhere to be seen (or heard) -- in four-part writing of ninth chords, one leaves out the fifth. At (c), the figure that applies to all three "extended" chords: keep the seventh below the newly added top note in ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords. At (d), the voiceleading for the rising line with waltz ninth, understood as at (e) splitting the ninth in two; the same at (f) in Schenkerian notation.

References:

Brown, Matthew. 2005. Explaining Tonality: Schenkerian Theory and Beyond. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Neumeyer, David. 2009. “Thematic Reading, Proto-Backgrounds, and Registral Transformations.” Music Theory Spectrum 31 (2): 284–324.

Yust, Jason. 2015. "Voice-Leading Transformation and Generative Theories of Tonal Structure." Music Theory Online 21/4: link