In May of this year, I started a series of posts that discussed compositions mentioned in the notes to my article "The Ascending Urlinie," this being the 30th year since its publication in the Journal of Music Theory. The two introductory posts are here: link; link. A further administrative post appeared in early September: link.

Since the series has necessarily been about Schenkerian analysis, I think it's important to stress here again that the blog is by no means restricted to that method or its issues. Referring to documents published on the Texas Scholar Works platform, I recently wrote "In this and other essays, a broader range of examples was made possible in part because the selection was not so constrained by abstract Schenkerian background models and their idealist voice leading. The result is a much better picture of musical practices over the several centuries separating 16th-century bicinia (two-voice pieces mainly for pedagogical use) from nineteenth century waltzes, polkas, and other instrumental and vocal compositions" (2017, 4). I have sometimes used a traditional Schenkerian method for pieces with clear focal tones that connect plausibly to rising cadence gestures, but equally or more often a freer model of reading lines and their patterns where I thought that provided better information. I have used my proto-background model when register, stable intervals and their transformations are particularly evident, and in the absence of analytic method I have used the simple, familiar model of style statistics and comparison where rising cadence gestures appear but their connections to pitch-design context aren't clear.

As the preceding suggests, although the hunt for rising cadence gestures began thirty years ago in an effort to justify and document the ascending Urlinie, it has evolved into a broader and more consequential historical project. That rising cadence gestures are far more than exceptions to the rule (even in narrowly constrained Schenkerian terms) has been obvious long since, but the historical narrative of these gestures in European and American music-making is a work in progress.

Reference:

Neumeyer, David. 2017. Ascending Cadence Gestures in Waltzes by Joseph Lanner. Link.

Saturday, September 30, 2017

Friday, September 29, 2017

JMT series, part 10 (Beethoven, Op. 22, III)

I intended this originally as a response to an article by Jason Yust; the menuet movement from the Piano Sonata, Op. 22, is the author's main example: link. There is, however, little to be said from the standpoint of traditional Schenkerian analysis, as Yust's goal is to rationalize the orthodox form of the theory, and therefore the analysis of Op, 22, III, assumes a priori Schenker's analysis from Free Composition and seeks to formalize it. Broadly, his position is similar to Matthew Brown's rationalization of Schenkerian theory (2005). Brown rejects the ascending Urlinie with a bit of circular reasoning; Yust doesn't engage it at all. The closest he comes is a critical note on the waltz ninth in this menuet's Urlinie: "Neumeyer (1987) . . . considers G to be an ascending passing tone rather than an upper neighbor. According to his interpretation, the G and A at the end of m. 7 are successive notes in a single voice, even though they both are sustained as part of the dominant ninth harmony over all of mm. 5–7" (2015, n33). More on that at the end of this post.

Yust does mention my article on proto-backgrounds (2009). As I noted above, he belongs among the "rationalizers" of Schenkerian theory (and so do I--in Neumeyer 2009, at least); he summarizes the earlier history very well (in paragraphs 0.1.1 & 0.1.2, and introductory paragraphs to subsequent sections). Although I can hardly claim to have offered a formalized theory in Neumeyer 2009, I did focus on a generative model (that is, building out from the background through transformations), which Yust also favors. Here is a sample, his Example 15; I have removed its analysis of the bass to show only the reading of the treble parts. The specific aim of the work is to portray contrapuntal melody (2 or more part-writing "voices") in a single diagram or figure (which presumably can then be subject to computerized comparisons). Level 0 is the "chord of nature" and is indistinguishable from one of my proto-backgrounds. At Level 1 the passing tone C is represented as a digression from the interval; then a second voice appears--as a hierarchically subordinate voice it is shown below the primary voice. Level 2, so to speak, harmonizes the two voices, drawing them together into a single diagram. The only comparison I can possibly make is to say that, in my view, Level 0 could just as easily have had the fourth F5-Bb5 instead of the third Bb4-D5.

In the details of his analysis, Yust brings out motivic thirds, beginning with the pick-up gesture. In my view, the fourth is more prominent, tying together accented notes at the beginning, F4-Bb4, and then being repeated. Stretched to a fifth -- one can hear the stretching in Enat5 -- the fourth can still be heard as a shadow within the compressed thirds that follow and continue throughout the continuation phrase. This theme, incidentally, is in the antecedent + continuation design, which Caplin regards as a hybrid but which I have found to be fundamental to 18th century galant style and have re-named the "galant theme" (link).

A reading using proto-backgrounds is not kind to my JMT analysis of the theme as using the registral variant, ^5-^6-(reg.) ^7-^8, since the stable interval would strongly imply/imagine ^5 (as F5) at the end. See below.

Thinking of the proto-background more abstractly, the initial fourth could be recovered -- circled notes below -- but the registral variant of the Urlinie would be undercut by this version, as well.

I still do think that a registral variant (link) is not difficult to hear in this theme and in the reprise (below), but it is obviously not compatible with a reading based on proto-backgrounds, which are after all biased in favor of registral definition and stability.

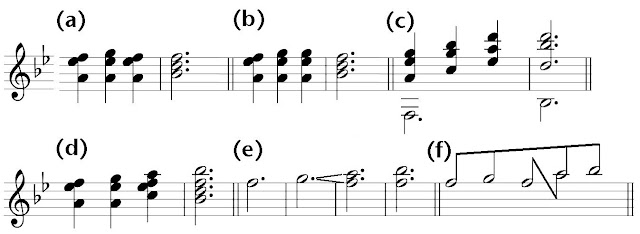

Note on the note: "Neumeyer (1987) . . . considers G to be an ascending passing tone rather than an upper neighbor. According to his interpretation, the G and A at the end of m. 7 are successive notes in a single voice, even though they both are sustained as part of the dominant ninth harmony over all of mm. 5–7" (Yust 2015, n33). I have written about the "waltz ninth" many times by now--here's a (link) to a recent post in this JMT series. Yust's criticism is the same as the one I've just made with respect to proto-backgrounds and does tend to undermine the registral variant. The waltz ninth is another matter. Nineteenth-century practice is broader--more creative and expressive--than eighteenth-century proscriptions. At (a), the ninth as neighbor note; at (b), the directly resolving ninth, a cliché in the waltz repertoire by no later than 1830. Note that the essential Schenkerian melodic note, C, is nowhere to be seen (or heard) -- in four-part writing of ninth chords, one leaves out the fifth. At (c), the figure that applies to all three "extended" chords: keep the seventh below the newly added top note in ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords. At (d), the voiceleading for the rising line with waltz ninth, understood as at (e) splitting the ninth in two; the same at (f) in Schenkerian notation.

References:

Brown, Matthew. 2005. Explaining Tonality: Schenkerian Theory and Beyond. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Neumeyer, David. 2009. “Thematic Reading, Proto-Backgrounds, and Registral Transformations.” Music Theory Spectrum 31 (2): 284–324.

Yust, Jason. 2015. "Voice-Leading Transformation and Generative Theories of Tonal Structure." Music Theory Online 21/4: link

Yust does mention my article on proto-backgrounds (2009). As I noted above, he belongs among the "rationalizers" of Schenkerian theory (and so do I--in Neumeyer 2009, at least); he summarizes the earlier history very well (in paragraphs 0.1.1 & 0.1.2, and introductory paragraphs to subsequent sections). Although I can hardly claim to have offered a formalized theory in Neumeyer 2009, I did focus on a generative model (that is, building out from the background through transformations), which Yust also favors. Here is a sample, his Example 15; I have removed its analysis of the bass to show only the reading of the treble parts. The specific aim of the work is to portray contrapuntal melody (2 or more part-writing "voices") in a single diagram or figure (which presumably can then be subject to computerized comparisons). Level 0 is the "chord of nature" and is indistinguishable from one of my proto-backgrounds. At Level 1 the passing tone C is represented as a digression from the interval; then a second voice appears--as a hierarchically subordinate voice it is shown below the primary voice. Level 2, so to speak, harmonizes the two voices, drawing them together into a single diagram. The only comparison I can possibly make is to say that, in my view, Level 0 could just as easily have had the fourth F5-Bb5 instead of the third Bb4-D5.

In the details of his analysis, Yust brings out motivic thirds, beginning with the pick-up gesture. In my view, the fourth is more prominent, tying together accented notes at the beginning, F4-Bb4, and then being repeated. Stretched to a fifth -- one can hear the stretching in Enat5 -- the fourth can still be heard as a shadow within the compressed thirds that follow and continue throughout the continuation phrase. This theme, incidentally, is in the antecedent + continuation design, which Caplin regards as a hybrid but which I have found to be fundamental to 18th century galant style and have re-named the "galant theme" (link).

A reading using proto-backgrounds is not kind to my JMT analysis of the theme as using the registral variant, ^5-^6-(reg.) ^7-^8, since the stable interval would strongly imply/imagine ^5 (as F5) at the end. See below.

Thinking of the proto-background more abstractly, the initial fourth could be recovered -- circled notes below -- but the registral variant of the Urlinie would be undercut by this version, as well.

I still do think that a registral variant (link) is not difficult to hear in this theme and in the reprise (below), but it is obviously not compatible with a reading based on proto-backgrounds, which are after all biased in favor of registral definition and stability.

Note on the note: "Neumeyer (1987) . . . considers G to be an ascending passing tone rather than an upper neighbor. According to his interpretation, the G and A at the end of m. 7 are successive notes in a single voice, even though they both are sustained as part of the dominant ninth harmony over all of mm. 5–7" (Yust 2015, n33). I have written about the "waltz ninth" many times by now--here's a (link) to a recent post in this JMT series. Yust's criticism is the same as the one I've just made with respect to proto-backgrounds and does tend to undermine the registral variant. The waltz ninth is another matter. Nineteenth-century practice is broader--more creative and expressive--than eighteenth-century proscriptions. At (a), the ninth as neighbor note; at (b), the directly resolving ninth, a cliché in the waltz repertoire by no later than 1830. Note that the essential Schenkerian melodic note, C, is nowhere to be seen (or heard) -- in four-part writing of ninth chords, one leaves out the fifth. At (c), the figure that applies to all three "extended" chords: keep the seventh below the newly added top note in ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords. At (d), the voiceleading for the rising line with waltz ninth, understood as at (e) splitting the ninth in two; the same at (f) in Schenkerian notation.

References:

Brown, Matthew. 2005. Explaining Tonality: Schenkerian Theory and Beyond. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Neumeyer, David. 2009. “Thematic Reading, Proto-Backgrounds, and Registral Transformations.” Music Theory Spectrum 31 (2): 284–324.

Yust, Jason. 2015. "Voice-Leading Transformation and Generative Theories of Tonal Structure." Music Theory Online 21/4: link

JMT series, part 7-2 (note 32)

This is the final post on music mentioned in the notes to my article "The Ascending Urlinie" (Journal of Music Theory, 1987). One additional post will return to the main text of the article, in response to a published analysis of the menuet in Beethoven's Piano Sonata, Opus 22.

Note 32 is about the registral variant ^5-^6-(reg.)^7-^8. Here is a link to the first post about this form: link.

In the note I mention Beethoven, String Quartet, op. 74, IV. Comment in the note: "where ^6 is somewhat extended."

In looking at the score of this quartet again, I see that my placement of this movement under the registral variant doesn't make sense. Since it is equally reasonable to hear movements I & III in terms of backgrounds with rising lines, I now suspect "IV" was an error, a typo for either "I" or "III." I intend to examine both earlier movements in the essay I am preparing based on the JMT-series blog posts. Here, however, I will keep attention on IV, whose rising line is prominent indeed.

The fourth movement is not an Allegro molto or Vivace finale, but instead a set of variations on an Allegretto theme. Here is the theme, and as the score and annotations show, there really is no doubt about the status of a focal tone ^5 and an ascending Urlinie at the end.

Five variations follow, plus a extended coda that starts out sounding like another variation. Variations 1-3 & 5 maintain the clarity of the rising line -- variation 2 (below) even gives to the first violin a simple reduction of the line! Variation 4 (not shown here) has a new melody in the first violin; it is centered on and closes on ^3 (G4).

A distinctive feature of the theme that is repeated in the first three variations is the old cadenza perfetta 6-8 figure appearing in both the half-cadence to G that ends the first strain and in the final cadence to the tonic.

The coda-qua-variation-6 (or variation 6 with coda character) can be read with the shapes of the theme in the first violin part, but the bass is strange indeed, so that it's hard to know quite what to make of the upper voice(s). The durations of the theme are maintained: bars 3-10 = theme, bars 1-8;

bars 11-14 = theme, bars 9-12, continuation phrase 1; bars 15-22 = theme, bars 13-20, expanded continuation phrase 2. The coda to this variation (or coda to this coda) runs an additional 53 bars. Within that the gesture of a "structural cadence" does appear in bars 39-42 -- see the bottom of the example below. At this moment, at least, the rising line is gone, but after the theme and five (six?) variations, the gesture seems rather hollow, a formula there because it's expected.

Note 32 is about the registral variant ^5-^6-(reg.)^7-^8. Here is a link to the first post about this form: link.

In the note I mention Beethoven, String Quartet, op. 74, IV. Comment in the note: "where ^6 is somewhat extended."

In looking at the score of this quartet again, I see that my placement of this movement under the registral variant doesn't make sense. Since it is equally reasonable to hear movements I & III in terms of backgrounds with rising lines, I now suspect "IV" was an error, a typo for either "I" or "III." I intend to examine both earlier movements in the essay I am preparing based on the JMT-series blog posts. Here, however, I will keep attention on IV, whose rising line is prominent indeed.

The fourth movement is not an Allegro molto or Vivace finale, but instead a set of variations on an Allegretto theme. Here is the theme, and as the score and annotations show, there really is no doubt about the status of a focal tone ^5 and an ascending Urlinie at the end.

Five variations follow, plus a extended coda that starts out sounding like another variation. Variations 1-3 & 5 maintain the clarity of the rising line -- variation 2 (below) even gives to the first violin a simple reduction of the line! Variation 4 (not shown here) has a new melody in the first violin; it is centered on and closes on ^3 (G4).

A distinctive feature of the theme that is repeated in the first three variations is the old cadenza perfetta 6-8 figure appearing in both the half-cadence to G that ends the first strain and in the final cadence to the tonic.

The coda-qua-variation-6 (or variation 6 with coda character) can be read with the shapes of the theme in the first violin part, but the bass is strange indeed, so that it's hard to know quite what to make of the upper voice(s). The durations of the theme are maintained: bars 3-10 = theme, bars 1-8;

bars 11-14 = theme, bars 9-12, continuation phrase 1; bars 15-22 = theme, bars 13-20, expanded continuation phrase 2. The coda to this variation (or coda to this coda) runs an additional 53 bars. Within that the gesture of a "structural cadence" does appear in bars 39-42 -- see the bottom of the example below. At this moment, at least, the rising line is gone, but after the theme and five (six?) variations, the gesture seems rather hollow, a formula there because it's expected.

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

JMT series, part 6c (note 31, the waltz ninth)

By the mid 1850s, when Jacques Offenbach began his prolific career as a composer of operetta and opera bouffe, rising cadence gestures were already well embedded in musical practice. (See my essay on Adolphe Adam's Le Châlet [1834]: link. The essay was based on posts to this blog; follow the labels for "Adam" or go to the first post in the series: link.)

The composition and production history of Offenbach's final work, Les contes de Hoffmann [The Tales of Hoffmann] is complicated, but there is no ambiguity about its most famous number, the Barcarolle "Belle nuit, ô nuit d'amour," number 13 in the four-act version of published French editions from the two decades after the composer's death. A duet for two sopranos, Giuletta, female lead of Act 3, and Nicklausse, Hoffmann's muse (a pants role), the soloists are joined by a chorus in the second half of the piece.

My comment in note 31: "^5 is prominent in the upper octave as a cover tone, also." Alas, here I was a bit optimistic about the status of the rising line. It is a distinctive figure to be sure--in fact, it is Giuletta's cadence line, and therefore ought to be given priority over the orchestra's plodding descent at that same place in the music. The orchestra's role in the gestures and topical expression of this particular number, however, is so strong that nowadays I have to regard the voice and orchestra as equals. That being the case, Giuletta's rising line is an inner voice, a "structural alto" to the orchestra's descending line from ^5. Details below.

I have shown just two systems from the vocal score. In the first, see the prominent A5 (^5), which of course has sounded many times before.

At (a) is the orchestra's descending line in the fifth octave (the keyboard reduction is corroborated by the full orchestral score, btw). At (b): Giuletta's ascending line, with ^6 (*) as the waltz ninth. At (c) Niklausse copies part of the orchestra's descent in the fourth octave. At (d) the curious detail of the second chorus alto repeated ^4-^3.

The composition and production history of Offenbach's final work, Les contes de Hoffmann [The Tales of Hoffmann] is complicated, but there is no ambiguity about its most famous number, the Barcarolle "Belle nuit, ô nuit d'amour," number 13 in the four-act version of published French editions from the two decades after the composer's death. A duet for two sopranos, Giuletta, female lead of Act 3, and Nicklausse, Hoffmann's muse (a pants role), the soloists are joined by a chorus in the second half of the piece.

My comment in note 31: "^5 is prominent in the upper octave as a cover tone, also." Alas, here I was a bit optimistic about the status of the rising line. It is a distinctive figure to be sure--in fact, it is Giuletta's cadence line, and therefore ought to be given priority over the orchestra's plodding descent at that same place in the music. The orchestra's role in the gestures and topical expression of this particular number, however, is so strong that nowadays I have to regard the voice and orchestra as equals. That being the case, Giuletta's rising line is an inner voice, a "structural alto" to the orchestra's descending line from ^5. Details below.

I have shown just two systems from the vocal score. In the first, see the prominent A5 (^5), which of course has sounded many times before.

At (a) is the orchestra's descending line in the fifth octave (the keyboard reduction is corroborated by the full orchestral score, btw). At (b): Giuletta's ascending line, with ^6 (*) as the waltz ninth. At (c) Niklausse copies part of the orchestra's descent in the fourth octave. At (d) the curious detail of the second chorus alto repeated ^4-^3.

Tuesday, September 26, 2017

JMT series, part 6b-3

This continues from yesterday's post to examine linear analyses of Beethoven, Symphony no. 1, III, and also to discuss its pervasive figure of the rising fourth.

In the previous post, I noted that Schachter's analysis of tonal structure was "bizarre, in my view radically un-Schenkerian." The sense of this assessment is apparent enough in the background/first middleground (63), which I have reproduced and annotated:

Far more (on traditional terms) mechanically and (in my view) musically plausible readings are shown below.

One can, of course, always read from ^3. This analysis takes the E5 in bar 3 as its focal tone--not unreasonable as it is the endpoint of the tonic prolongation in the opening phrase. The reading positions the "flat-key" area within a dominant prolongation, which matches our expectations about tonal design and formal functions. And the ending is conventional too, though ^2 must be implied (not shown that way, here) if one is taking the first violins, first oboe, and first flute as the line. There is a simple ^3-^2-^1 in the first horn and viola. Details of this reading may be found on my Google Drive page: link.

The traditional reading from ^5 fits the music as well as the one from ^3, with the exception that ^5 appears in the first obviously non-tonic moment (I've whisked that away in the graph, but you can see it in the score -- top of the previous post). This graph also shows more clearly that V in the retransition has been replaced by iii (as iii6/4).

A descending line from ^8 is not possible, but one can hear a stable ^8 -- surrounded by neighbor notes -- if one takes the strongest shape of the opening, the rising fourth motive, and chooses its goal tone as a long range focal tone. Details of this reading may be found on my Google Drive page: link.

The rising fourth motive and the persistent register play make a reading with a proto-background quite convincing. For more on proto-backgrounds, see my essay on Texas Scholar Works: link.

Finally, a reading meant to support the previous two, but I think also quite strong on its own. The fourth motive is stated three times, as three 2 bar ideas, in the first strain. A cadential gesture finishes. In the B section, the motive is continually present, as an obvious inverse, then expanded to a sixth in the approach to the cadence on bII. After that, the original and inverse are combined in the "codetta" to the Db cadence. A distorted version in the retransition is followed by the 14-bar expansion of the main theme in the reprise (bars 45-58), where the motivic idea is heard six times before the cadence formula. In the second half of the coda the rising motive and the falling melodic formula are opposed.

References:

Schachter, Carl. 2000. “Playing What the Composer Didn’t Write: Analysis and Rhythmic Aspects of Performance.” In Essays in Honor of Jacob Lateiner, edited by Bruce Brubaker and Jane Gottlieb, 47-68. Pendragon.

In the previous post, I noted that Schachter's analysis of tonal structure was "bizarre, in my view radically un-Schenkerian." The sense of this assessment is apparent enough in the background/first middleground (63), which I have reproduced and annotated:

Far more (on traditional terms) mechanically and (in my view) musically plausible readings are shown below.

One can, of course, always read from ^3. This analysis takes the E5 in bar 3 as its focal tone--not unreasonable as it is the endpoint of the tonic prolongation in the opening phrase. The reading positions the "flat-key" area within a dominant prolongation, which matches our expectations about tonal design and formal functions. And the ending is conventional too, though ^2 must be implied (not shown that way, here) if one is taking the first violins, first oboe, and first flute as the line. There is a simple ^3-^2-^1 in the first horn and viola. Details of this reading may be found on my Google Drive page: link.

The traditional reading from ^5 fits the music as well as the one from ^3, with the exception that ^5 appears in the first obviously non-tonic moment (I've whisked that away in the graph, but you can see it in the score -- top of the previous post). This graph also shows more clearly that V in the retransition has been replaced by iii (as iii6/4).

A descending line from ^8 is not possible, but one can hear a stable ^8 -- surrounded by neighbor notes -- if one takes the strongest shape of the opening, the rising fourth motive, and chooses its goal tone as a long range focal tone. Details of this reading may be found on my Google Drive page: link.

The rising fourth motive and the persistent register play make a reading with a proto-background quite convincing. For more on proto-backgrounds, see my essay on Texas Scholar Works: link.

Finally, a reading meant to support the previous two, but I think also quite strong on its own. The fourth motive is stated three times, as three 2 bar ideas, in the first strain. A cadential gesture finishes. In the B section, the motive is continually present, as an obvious inverse, then expanded to a sixth in the approach to the cadence on bII. After that, the original and inverse are combined in the "codetta" to the Db cadence. A distorted version in the retransition is followed by the 14-bar expansion of the main theme in the reprise (bars 45-58), where the motivic idea is heard six times before the cadence formula. In the second half of the coda the rising motive and the falling melodic formula are opposed.

The three main cadences (not counting the one in Db major or bars 67-76) have versions of the same rhythmic figure and falling shape. At (a), the accented bar is on V/V. At (b), it is on the cadential dominant 6/4, but at (c) it is on the tonic -- the cadence came before it this time. It is this motivically driven dramatic plan that allows us to hear the final bars and not the earlier formula as the proper end of this menuetto/scherzo.

References:

Schachter, Carl. 2000. “Playing What the Composer Didn’t Write: Analysis and Rhythmic Aspects of Performance.” In Essays in Honor of Jacob Lateiner, edited by Bruce Brubaker and Jane Gottlieb, 47-68. Pendragon.

Monday, September 25, 2017

JMT series, part 6b-2 (note 31, the waltz ninth)

Beethoven, Symphony no. 1, Scherzo. As we saw in the earlier post, part 6a-1, the scherzo of the Second Symphony clearly draws on the "waltz ninth" device -- that is, positioning both ^6 and ^7 over the dominant. The Menuetto in the First Symphony is equally clear in its final cadence—see below—but the analysis of the background will not be as simple.

My comment in the note: "if the structural cadence is taken to be at the end and not in mm. 57-58." That was a somewhat risky statement, as the usual formal functions would certainly point to bars 57-58. In an essay on analysis and performance (that is, recordings), Carl Schachter predictably took me to task on that point: "The phrase that begins with m. 52 represents the Menuet’s structural cadence, closing into the final structural tonic in m. 58. The emphasis on ^1 starting in m. 58 is so unremitting that we must regard the closing measures as a coda; David Neumeyer's suggestion that the structural close might be at the very end, with an ascending Urlinie ^5-^6-^7-^8 is not very plausible, at least to my ear." On the face of it--thinking of it in terms of 18th century formal function clichés--he is right. Here is the reprise (in Singer's transcription) with annotations following Caplin. Everything is "textbook": the reprise offers a complete theme (a 14-bar sentence) with a PAC in the tonic at the end, after which a pedal point tonic runs along for several bars before giving way to accelerated V-I figures culminating in one last emphatic cadence. The two cadences are boxed.

Nevertheless, this menuet/scherzo strikes me as an early instance in which the rising gesture, common to codas in this period, begins to contest priority with the standard structural cadence that complies with the expected formal functions. As I have written elsewhere in this blog and in essays, this change was in part due to the historical shift away from partimento practices; that is to say, from the Italian models that had dominated European music for well over a century. The muddling of the formal functions themselves was the principal route for a changed role for rising gestures, including the rising line, as we saw in the scherzo of the Second Symphony. Beethoven doesn't rethink cadence and coda so fundamentally in the First Symphony—basically, I agree with Schachter's objection as based on routine formal functions—but I will argue for the final bars as the culmination of a developmental process that bypasses—skips over—the structural cadence.

I am, however, obliged to disagree almost entirely with Schachter's Schenkerian analysis, which is, to put it mildly, bizarre, with chromatic parallels in the first middleground, notes plucked out of the bass when they don't need to be, and an imagined ^3 and ^2 in the background descent.

Schachter describes his essay as a study in “how an awareness of large-scale connections can help one in working out appropriate strategies for pacing, accentuation, and other rhythmic details of performance. I shall be concentrating on a few small details, but they are details whose shaping depends upon a conception of the work as a whole, for these details—far from having a simple location in their immediate environments—reverberate throughout the entire piece. . . . These intimations of the whole suggest to me ways of playing that one might not adopt if the detail were of purely local significance” (48).

He looks at three pieces on these terms, the last of them being the scherzo in the First Symphony. A “Menuetto” in name only, this movement is in a tempo fast enough to push it well out of the realm of dance music—the topical basis of the third movement in 18th century symphonies, including Mozart’s and (most of) Haydn’s—toward autonomous instrumental music. Or, better said, toward a different and largely new topical association. Had he followed 18th century conventions, Beethoven would have notated the movement in 6/8 time, as a gigue.

Beethoven, Symphony no. 1, III, opening (reduction):

Notation of the opening melody as a gigue:

As we know now, in the 18th century notation itself had strong topical associations (Allanbrook 1983; cited in Mirka 2014). Listening to the examples above, it is obvious that the "Menuetto" is no jig either, practical or stylized: it is frenetic, quixotic, sometimes dramatic, and sharply profiled in dynamics, register, and treatment of instruments. In other words, the topic is new, perhaps born out of the late symphonies of Haydn or perhaps an intensified (but also warped), stylized version of the German dance (Deutscher), the faster and usually louder alter ego of the Ländler.

We will pass through the early history of "scherzo" quickly. It apparently originated about 1600 as a verse form and therefore was linked to vocal music. When the term moved over into instrumental music later in the century and in the early 18th century, it almost always designated a movement in a multi-movement set, in duple meter (most often 2/4) and without trio. It may well have been an alternative title to the ambiguous "aria." Haydn in his string quartets, opus 33, used the term deliberately to designate movements that take the place of the menuet in a sonata cycle, and Beethoven eventually followed suit. According to Hugh McDonald, "it was Beethoven who established the scherzo as a regular alternative to the minuet and as a classic movement-type. From his earliest works the scherzo appears . . . in place of the minuet, and he took the term literally by giving the movement a light and often humorous tone." Of the pieces immediately preceding the First Symphony, which is Opus 26, four (opuses 20, 23-25) contain scherzi. Here are incipits:

From the Septet, op. 20, in Carl Czerny's reduction. As in opus 26, instrumentation, register, dynamics, and meter/accent are all in play.

From the Violin Sonata, op. 23. "Scherzoso" here is obviously a qualifier for "Andante," not a topic on its own.

From the Violin Sonata, op. 24:

From the Serenade, op. 25 in a later reduction:

And here are incipits from pieces following the First Symphony:

From the Piano Sonata, op. 28:

From the String Quintet, op. 29 in a later reduction:

From the Violin Sonata, op. 30n2:

Not surprisingly, the issue at hand for Schachter with respect to performance is hypermeter; like Beethoven’s later scherzi, the First Symphony's "Menuetto" is written in 3/4 meter but without question each bar is like a beat. Schachter focuses on the problem of the proper downbeat for the hypermeter: is it in bar 1 or bar 2? I have rewritten the opening melody in 6/4 meter to try to capture these two versions:

To Schachter, "b" is the proper meter, and "a" is a "shadow meter," maintained sufficiently that it *could* become the primary meter by means of later developments in the movement. The drama of the piece is the conflict between these two and its late resolution (in the reprise). Engaging though the account is on its own terms, it founders on two points: (a) as I said earlier, a bizarre, in my view radically un-Schenkerian reading of tonal structure; (b) in Schachter's final recommendation, small fruit from all the detailed analysis: he suggests making the accents of bars 3 & 4 roughly equal, the larger gestures of the reprise then bringing the metric conflict to resolution. Those larger gestures were going to happen anyway, the aural legacy of subtle differences in the opening measures being negligible.

The figure of the rising fourth motive, on the other hand, will remain memorable throughout.

I'll discuss point (a) in tomorrow's post.

References:

Allanbrook, Wye. 1983. Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart. University of Chicago Press.

McDonald, Hugh, and Tilden A. Russell. "Scherzo." Oxford Music Online.

Mirka, Danuta. 2014. "Topics and Meter." In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, 357-380.

Schachter, Carl. 2000. “Playing What the Composer Didn’t Write: Analysis and Rhythmic Aspects of Performance.” In Essays in Honor of Jacob Lateiner, edited by Bruce Brubaker and Jane Gottlieb, 47-68. Pendragon.

My comment in the note: "if the structural cadence is taken to be at the end and not in mm. 57-58." That was a somewhat risky statement, as the usual formal functions would certainly point to bars 57-58. In an essay on analysis and performance (that is, recordings), Carl Schachter predictably took me to task on that point: "The phrase that begins with m. 52 represents the Menuet’s structural cadence, closing into the final structural tonic in m. 58. The emphasis on ^1 starting in m. 58 is so unremitting that we must regard the closing measures as a coda; David Neumeyer's suggestion that the structural close might be at the very end, with an ascending Urlinie ^5-^6-^7-^8 is not very plausible, at least to my ear." On the face of it--thinking of it in terms of 18th century formal function clichés--he is right. Here is the reprise (in Singer's transcription) with annotations following Caplin. Everything is "textbook": the reprise offers a complete theme (a 14-bar sentence) with a PAC in the tonic at the end, after which a pedal point tonic runs along for several bars before giving way to accelerated V-I figures culminating in one last emphatic cadence. The two cadences are boxed.

Nevertheless, this menuet/scherzo strikes me as an early instance in which the rising gesture, common to codas in this period, begins to contest priority with the standard structural cadence that complies with the expected formal functions. As I have written elsewhere in this blog and in essays, this change was in part due to the historical shift away from partimento practices; that is to say, from the Italian models that had dominated European music for well over a century. The muddling of the formal functions themselves was the principal route for a changed role for rising gestures, including the rising line, as we saw in the scherzo of the Second Symphony. Beethoven doesn't rethink cadence and coda so fundamentally in the First Symphony—basically, I agree with Schachter's objection as based on routine formal functions—but I will argue for the final bars as the culmination of a developmental process that bypasses—skips over—the structural cadence.

I am, however, obliged to disagree almost entirely with Schachter's Schenkerian analysis, which is, to put it mildly, bizarre, with chromatic parallels in the first middleground, notes plucked out of the bass when they don't need to be, and an imagined ^3 and ^2 in the background descent.

Schachter describes his essay as a study in “how an awareness of large-scale connections can help one in working out appropriate strategies for pacing, accentuation, and other rhythmic details of performance. I shall be concentrating on a few small details, but they are details whose shaping depends upon a conception of the work as a whole, for these details—far from having a simple location in their immediate environments—reverberate throughout the entire piece. . . . These intimations of the whole suggest to me ways of playing that one might not adopt if the detail were of purely local significance” (48).

He looks at three pieces on these terms, the last of them being the scherzo in the First Symphony. A “Menuetto” in name only, this movement is in a tempo fast enough to push it well out of the realm of dance music—the topical basis of the third movement in 18th century symphonies, including Mozart’s and (most of) Haydn’s—toward autonomous instrumental music. Or, better said, toward a different and largely new topical association. Had he followed 18th century conventions, Beethoven would have notated the movement in 6/8 time, as a gigue.

Beethoven, Symphony no. 1, III, opening (reduction):

Notation of the opening melody as a gigue:

As we know now, in the 18th century notation itself had strong topical associations (Allanbrook 1983; cited in Mirka 2014). Listening to the examples above, it is obvious that the "Menuetto" is no jig either, practical or stylized: it is frenetic, quixotic, sometimes dramatic, and sharply profiled in dynamics, register, and treatment of instruments. In other words, the topic is new, perhaps born out of the late symphonies of Haydn or perhaps an intensified (but also warped), stylized version of the German dance (Deutscher), the faster and usually louder alter ego of the Ländler.

We will pass through the early history of "scherzo" quickly. It apparently originated about 1600 as a verse form and therefore was linked to vocal music. When the term moved over into instrumental music later in the century and in the early 18th century, it almost always designated a movement in a multi-movement set, in duple meter (most often 2/4) and without trio. It may well have been an alternative title to the ambiguous "aria." Haydn in his string quartets, opus 33, used the term deliberately to designate movements that take the place of the menuet in a sonata cycle, and Beethoven eventually followed suit. According to Hugh McDonald, "it was Beethoven who established the scherzo as a regular alternative to the minuet and as a classic movement-type. From his earliest works the scherzo appears . . . in place of the minuet, and he took the term literally by giving the movement a light and often humorous tone." Of the pieces immediately preceding the First Symphony, which is Opus 26, four (opuses 20, 23-25) contain scherzi. Here are incipits:

From the Septet, op. 20, in Carl Czerny's reduction. As in opus 26, instrumentation, register, dynamics, and meter/accent are all in play.

From the Violin Sonata, op. 23. "Scherzoso" here is obviously a qualifier for "Andante," not a topic on its own.

From the Violin Sonata, op. 24:

From the Serenade, op. 25 in a later reduction:

And here are incipits from pieces following the First Symphony:

From the Piano Sonata, op. 28:

From the String Quintet, op. 29 in a later reduction:

From the Violin Sonata, op. 30n2:

Not surprisingly, the issue at hand for Schachter with respect to performance is hypermeter; like Beethoven’s later scherzi, the First Symphony's "Menuetto" is written in 3/4 meter but without question each bar is like a beat. Schachter focuses on the problem of the proper downbeat for the hypermeter: is it in bar 1 or bar 2? I have rewritten the opening melody in 6/4 meter to try to capture these two versions:

The figure of the rising fourth motive, on the other hand, will remain memorable throughout.

I'll discuss point (a) in tomorrow's post.

References:

Allanbrook, Wye. 1983. Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart. University of Chicago Press.

McDonald, Hugh, and Tilden A. Russell. "Scherzo." Oxford Music Online.

Mirka, Danuta. 2014. "Topics and Meter." In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, 357-380.

Schachter, Carl. 2000. “Playing What the Composer Didn’t Write: Analysis and Rhythmic Aspects of Performance.” In Essays in Honor of Jacob Lateiner, edited by Bruce Brubaker and Jane Gottlieb, 47-68. Pendragon.

Sunday, September 24, 2017

JMT series, part 9-2 (Telemann)

n34: This double treatment of the fourth ^5 to ^8. . . .

Telemann, Harmonischer Gottesdienst, cantata no. 9, first aria. My note: where affect and tonal design are nicely linked, as the text is “Liebe, die von Himmel stammet, steigt auch wieder Himmel an" [Love that comes [down] from Heaven, ascends to Heaven again"].

My source was a facsimile of the first score edition, downloaded from IMSLP. I edited the voice part to put it in a modern treble clef.

The violin introduces the two contrasting figures that mimic the text: at (a) descending in eighth notes; at (b) rising sixteenth notes. The voice repeats them -- see (a) and (b) in the third system. At (c) the voice reaches ^7-^8 to end the phrase ("Himmel an") but the harmony undercuts the cadence, which arrives shortly after with the traditional dominant level cadence midway through the A-section of a da capo aria -- see boxed notes in the fourth system. Beneath the score find the details of the mirror Urlinie reading.

In the second half of the A-section, the violin has a short ritornello on the descending figure, and the voice repeats it, turning quickly toward the minor (another cliché of the da capo aria). The subsequent ascent -- at (d) is expanded: a continuous rise to the tonic ^8 (Eb5) is again undercut by a deceptive close -- at (e) -- which enables another phrase full and a strong close. I have included the violin's closing ritornello and the beginning bars of the B-section for sake of context.

Here are the details of the mirror Urlinie reading:

Telemann, Harmonischer Gottesdienst, cantata no. 9, first aria. My note: where affect and tonal design are nicely linked, as the text is “Liebe, die von Himmel stammet, steigt auch wieder Himmel an" [Love that comes [down] from Heaven, ascends to Heaven again"].

My source was a facsimile of the first score edition, downloaded from IMSLP. I edited the voice part to put it in a modern treble clef.

The violin introduces the two contrasting figures that mimic the text: at (a) descending in eighth notes; at (b) rising sixteenth notes. The voice repeats them -- see (a) and (b) in the third system. At (c) the voice reaches ^7-^8 to end the phrase ("Himmel an") but the harmony undercuts the cadence, which arrives shortly after with the traditional dominant level cadence midway through the A-section of a da capo aria -- see boxed notes in the fourth system. Beneath the score find the details of the mirror Urlinie reading.

In the second half of the A-section, the violin has a short ritornello on the descending figure, and the voice repeats it, turning quickly toward the minor (another cliché of the da capo aria). The subsequent ascent -- at (d) is expanded: a continuous rise to the tonic ^8 (Eb5) is again undercut by a deceptive close -- at (e) -- which enables another phrase full and a strong close. I have included the violin's closing ritornello and the beginning bars of the B-section for sake of context.

Saturday, September 23, 2017

JMT series, part 9-1 (note 34, mirror Urlinie)

n34: my note: The double treatment of the fourth ^5 to ^8 occurs also in Saint Saëns, Le Carnival des animaux, “Le cygne.”

The melody is distinguished by an expressive leap at the end of the first long phrase; the scale leads us to expect G, but we hear B instead. The original solo is for 'cello; the violin transcription of this phrase is as follows:

From this, I might read any of three plausible backgrounds for a traditional Schenkerian analysis. Version (a) acknowledges B as ^3; that returns (not shown) in the reprise and descends in the final cadence [I will show details in a moment]. Version (b) is the mirror Urlinie; it takes B as a cover tone and works out a longer descent/ascent pair over the course of the reprise. Version (c) is more radical: it assumes the octave line itself -- or even more broadly the motive of the slightly ornamented scale gesture -- as a first middleground, with the neighbor ^8^7^8 as the background. As with version (a), the ascent and close are concentrated in the final cadence.

Here are details of the three readings, using the 'cello solo part. At the bottom of the post is a chordal reduction of the entire piece, again using tones from the violin part.

The reading from ^3 is clear enough. The registrally correct G4 in the leading-tone third line has to be inferred from the sounding G3.

The reading of particular interest here -- the mirror Urlinie -- is not really all that much more complicated. In the unfolded third of the opening melody, the lower note is considered primary this time. The descent/ascent pair are presented quite plainly across the space of the final phrase.

Finally, the reading with ^8-^7-^8 and a middleground ascending octave line. The background neighbor-note figure creates a very simple tonal frame. The middleground octave line provides a motivic parallel to the ascending eighth-note line in the melody (see the boxed notes -- these of course also occur in the third bar of the opening melody).

For reference a chordal reduction. The design is a small ternary form: A = 1-8; B = 9-17; A' = 18 to the end. The harmony moves from I to iii in the A-section, then by sequence eventually reaching v or V. The reprise works out a broadly cadential progression.

The other piece mentioned in note 34 as having a mirror Urlinie -- a Telemann aria -- will be examined in tomorrow's post.

The melody is distinguished by an expressive leap at the end of the first long phrase; the scale leads us to expect G, but we hear B instead. The original solo is for 'cello; the violin transcription of this phrase is as follows:

From this, I might read any of three plausible backgrounds for a traditional Schenkerian analysis. Version (a) acknowledges B as ^3; that returns (not shown) in the reprise and descends in the final cadence [I will show details in a moment]. Version (b) is the mirror Urlinie; it takes B as a cover tone and works out a longer descent/ascent pair over the course of the reprise. Version (c) is more radical: it assumes the octave line itself -- or even more broadly the motive of the slightly ornamented scale gesture -- as a first middleground, with the neighbor ^8^7^8 as the background. As with version (a), the ascent and close are concentrated in the final cadence.

The reading from ^3 is clear enough. The registrally correct G4 in the leading-tone third line has to be inferred from the sounding G3.

The reading of particular interest here -- the mirror Urlinie -- is not really all that much more complicated. In the unfolded third of the opening melody, the lower note is considered primary this time. The descent/ascent pair are presented quite plainly across the space of the final phrase.

Finally, the reading with ^8-^7-^8 and a middleground ascending octave line. The background neighbor-note figure creates a very simple tonal frame. The middleground octave line provides a motivic parallel to the ascending eighth-note line in the melody (see the boxed notes -- these of course also occur in the third bar of the opening melody).

For reference a chordal reduction. The design is a small ternary form: A = 1-8; B = 9-17; A' = 18 to the end. The harmony moves from I to iii in the A-section, then by sequence eventually reaching v or V. The reprise works out a broadly cadential progression.

The other piece mentioned in note 34 as having a mirror Urlinie -- a Telemann aria -- will be examined in tomorrow's post.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)