Franz Waxman wrote the underscore for Rebecca (1940; produced by Selznick, directed by Hitchcock). Early in the film we hear the "Hotel Lobby Waltz." A reduced version of the tune in transcription, along with chord symbols, is given below. Some bars of the reduction have all the notes, others have a principal note only. As the transcription shows, the final cadence rises.

Here is a formal Schenkerian sketch, with annotations that mark action in the film. "Exterior" refers to the exterior of the hotel; "interior" is the cut to the hotel lobby. "He" of course is Laurence Olivier in character as Maxim de Winter. "On reprise" refers to the reprise following a trio: the overall design is waltz (AABA)-trio-waltz. (The "Hotel Lobby Waltz," by the way, segues directly into the waltzes by Lanner and Strauss used in the breakfast scene.)

The waltz has a trio, which is sketched below.

A middleground/background sketch of the entire cue is here. The striking thing about the piece is certainly the "naturalization" of add6, so that the Urlinie is not ^5-^6-^7-^8 but only ^6-^7-^8.

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

Monday, February 27, 2017

Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, 1910s and 1920s (4), continued

Yesterday I wrote about two numbers in The Vagabond King (music by Rudolf Friml, 1925). As a postscript, here is a number from Friml's version of The Three Musketeers (1928). Another march, like the drinking song in The Vagabond King, this one is a vigorous affirmation of D'Artagnan's (and the Musketeers') loyalty to king and country.

Focus on ^5 is very strong, but in the musical example below note the equally strong internal rising figure in the accompaniment.

In the cadence, a remarkable wedge figure takes the bass down through the octave and the melody up. The melody is easily divided at the focal note (C5, circled), with fifth below and fourth above, so that an ascending line ^5-^6-^7-^nat7-^8 is readily heard.

The entr'acte between Acts I and II is this same composition, but the orchestral accompaniment only: see the opening below. Of course, the same rising line ends, as above.

As a postscript to the postscript, here is the ending of number 24, a duet for Constance and D'Artagnan that parallels the one between Katherine and Villon that I discussed in yesterday's post.

Note especially the optional ending (arrow) that keeps the rising line in its "obligatory register."

Focus on ^5 is very strong, but in the musical example below note the equally strong internal rising figure in the accompaniment.

In the cadence, a remarkable wedge figure takes the bass down through the octave and the melody up. The melody is easily divided at the focal note (C5, circled), with fifth below and fourth above, so that an ascending line ^5-^6-^7-^nat7-^8 is readily heard.

The entr'acte between Acts I and II is this same composition, but the orchestral accompaniment only: see the opening below. Of course, the same rising line ends, as above.

As a postscript to the postscript, here is the ending of number 24, a duet for Constance and D'Artagnan that parallels the one between Katherine and Villon that I discussed in yesterday's post.

Note especially the optional ending (arrow) that keeps the rising line in its "obligatory register."

Sunday, February 26, 2017

Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, 1910s and 1920s (4)

Rudolf Friml's The Vagabond King was produced on Broadway in 1925. It remains the composer's best-known work. Wikipedia link to the musical: link. Because the music is still under copyright, I have reproduced only very brief excerpts with annotations.

The book for this musical is a heavily fictionalized and romanticized story about François Villon, taken from a popular novel and play, If I Were King (1901), by Justin McCarthy. In fact, about the only thing historical is the character of François Villon and his engagement in criminal activities. That he is presented as a swashbuckling type who would eventually put his skills to positive use fits a well-established stereotype in the nineteenth and early twentieth century stage and film repertoires (think Zorro, Captain Blood, Robin Hood [as played by Errol Flynn], and many others).

Briefly and very roughly, Louis XI condemns Villon to death; the latter raises the Paris rabble to defeat the besieging Burgundians; Villon is condemned anyway; Katherine de Vaucey offers to die instead; the King pardons -- and exiles -- them both. (The Wikipedia article has a good synopsis.)

Number 4 is a comic drinking song -- or one might say, a drinking march: note the "Marziale" annotation for the refrain, whose opening melody is shown here:

The second half of the refrain is a steady ascending approach to the cadence. The first motive offers a "flagon" (below) then expanding repetitions of the motive move upward -- the steps taken are shown at the right in the first system -- until we reach Ab5 and A5 (second system) and "an ocean of wine."

"Tomorrow" (n12) is a romantic duet for Katherine and Villon. Villon sings the verse and refrain, then Katherine sings the verse (to new words), and finally he repeats the refrain while she adds a descant part -- see the opening of this last below. Note the persistently rising figure in the descant, while the main melody hovers about ^3 (as C5).

In the cadence, a complicated set of figures emerges out of this pairing. In the main melody, C5 -- see circled note almost at the end of Villon's part -- substitutes for ^2 in an abstract third-line we would trace back to the focal note C5 at the beginning. When ^3 substitutes for ^2 over the dominant seventh chord, the V13 effect is created -- one can trace its use back at least to 1840. At the same time, the melody moves much more concretely up from ^5 -- see boxed notes in Villon's part. The double arrows show the complications: Katherine picks up ^5 an octave higher (Eb5) and doubles the chromatic progression and the tonic-note ending (boxed notes), but she uses the common substitution of ^5 for ^7 in the rising line. The progression, however, is literally given in the accompaniment, as Eb4-E4-F4-G4-Ab4 (see the sequence of arrows in the accompaniment).

The book for this musical is a heavily fictionalized and romanticized story about François Villon, taken from a popular novel and play, If I Were King (1901), by Justin McCarthy. In fact, about the only thing historical is the character of François Villon and his engagement in criminal activities. That he is presented as a swashbuckling type who would eventually put his skills to positive use fits a well-established stereotype in the nineteenth and early twentieth century stage and film repertoires (think Zorro, Captain Blood, Robin Hood [as played by Errol Flynn], and many others).

Briefly and very roughly, Louis XI condemns Villon to death; the latter raises the Paris rabble to defeat the besieging Burgundians; Villon is condemned anyway; Katherine de Vaucey offers to die instead; the King pardons -- and exiles -- them both. (The Wikipedia article has a good synopsis.)

Number 4 is a comic drinking song -- or one might say, a drinking march: note the "Marziale" annotation for the refrain, whose opening melody is shown here:

The second half of the refrain is a steady ascending approach to the cadence. The first motive offers a "flagon" (below) then expanding repetitions of the motive move upward -- the steps taken are shown at the right in the first system -- until we reach Ab5 and A5 (second system) and "an ocean of wine."

"Tomorrow" (n12) is a romantic duet for Katherine and Villon. Villon sings the verse and refrain, then Katherine sings the verse (to new words), and finally he repeats the refrain while she adds a descant part -- see the opening of this last below. Note the persistently rising figure in the descant, while the main melody hovers about ^3 (as C5).

In the cadence, a complicated set of figures emerges out of this pairing. In the main melody, C5 -- see circled note almost at the end of Villon's part -- substitutes for ^2 in an abstract third-line we would trace back to the focal note C5 at the beginning. When ^3 substitutes for ^2 over the dominant seventh chord, the V13 effect is created -- one can trace its use back at least to 1840. At the same time, the melody moves much more concretely up from ^5 -- see boxed notes in Villon's part. The double arrows show the complications: Katherine picks up ^5 an octave higher (Eb5) and doubles the chromatic progression and the tonic-note ending (boxed notes), but she uses the common substitution of ^5 for ^7 in the rising line. The progression, however, is literally given in the accompaniment, as Eb4-E4-F4-G4-Ab4 (see the sequence of arrows in the accompaniment).

Saturday, February 25, 2017

Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, 1910s and 1920s (3)

The chorus is a straightforward double period where the melody is controlled by obvious stepwise figures: Bars 1, 3, and 5 below will illustrate. The ending, with the ascent from ^5, is at the bottom of the page.

Friday, February 24, 2017

Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, 1910s and 1920s (2)

Albert von Tilzer was a contemporary of Joseph E. Howard and an equally successful song writer, known best now for "Take Me Out to the Ballgame." "Down Where the Swanee Flows" (1916) is typical of a sentimental strain of "Southern songs" that, yes, does go back as far as Stephen Foster in the mid-19th century. Link to the sheet music on the Lester Levy Collection website: link.

The design of the chorus is 32 bars, but what I am tempted to call "through-composed" -- that is, every eight-bar unit is different, so ABCD (most certainly not the stereotypical AABA). The opening defines two spaces, Eb4-Bb4 and Bb4 (here, C5)-Eb5. The lower of the two predominates throughout, which permits reading Bb4 (or ^5) as a focal tone and the progression to the cadence in the final 8-bar unit both clear and simple (second example below).

(Chorus ending)

The design of the chorus is 32 bars, but what I am tempted to call "through-composed" -- that is, every eight-bar unit is different, so ABCD (most certainly not the stereotypical AABA). The opening defines two spaces, Eb4-Bb4 and Bb4 (here, C5)-Eb5. The lower of the two predominates throughout, which permits reading Bb4 (or ^5) as a focal tone and the progression to the cadence in the final 8-bar unit both clear and simple (second example below).

(Chorus ending)

Thursday, February 23, 2017

Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, 1910s and 1920s (1)

The Library of Congress and several other collections have digitized and made available an enormous number of musical compositions published in the United States before 1923. In this series, I will comment on a few with ascending cadence gestures.

Herbert Stothart is well-known as the director of the music department at the MGM studio in the 1930s and 1940s. He came to Hollywood, along with a good many others, from Broadway, where he had established a reputation as an orchestrator and composer by the early 1920s.

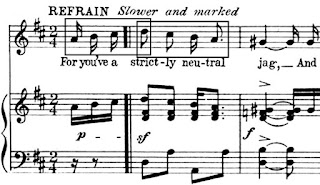

The song "Strictly Neutral Jag," co-written with Joseph E. Howard for the show "The Girl of Tomorrow" (1915) in which the song was featured. (All this according to the cover page. I was unable to find anything more on the show. Howard was a Tin Pan Alley composer who wrote "Hello Ma' Baby," among other well-known tunes. Howard's name is listed first on the cover and first page of the score.) The sentiment of the song's subtitle "A Dramatic Appeal with Music" was for American neutrality in World War I, by no means an uncommon view in 1915. "Jag," of course is a play on "rag." The music can be found on the Lester Levy Collection website: link.

The opening of the chorus (refrain) sets up an interval frame ^5-^8, both rising and falling (boxed notes).

The potential of this frame is eventually realized in the close. The chorus is not in the familiar 32-bar AABA design: it is a double period whose first unit is a sentence (see the continuation phrase in the example below -- first four bars) and whose second unit (consequent) is expanded by 4 bars -- those extra bars appear in the second example below. As the opening bar above (repeated at the end of the first example below, with ^1) shows, D5 is well defined as a focal note. Scale degree ^2 is reached at the end of the first unit, and I suppose could be called an interruption, but I have become increasingly skeptical of that term and would find neighbor note quite sufficient: so ^1 -- ^2 -- ^1.

In the consequent D5 descends by sequence down to B4 (not A4) and then rises again to C#5-D5 in the cadence.

Chorus ending:

Herbert Stothart is well-known as the director of the music department at the MGM studio in the 1930s and 1940s. He came to Hollywood, along with a good many others, from Broadway, where he had established a reputation as an orchestrator and composer by the early 1920s.

The song "Strictly Neutral Jag," co-written with Joseph E. Howard for the show "The Girl of Tomorrow" (1915) in which the song was featured. (All this according to the cover page. I was unable to find anything more on the show. Howard was a Tin Pan Alley composer who wrote "Hello Ma' Baby," among other well-known tunes. Howard's name is listed first on the cover and first page of the score.) The sentiment of the song's subtitle "A Dramatic Appeal with Music" was for American neutrality in World War I, by no means an uncommon view in 1915. "Jag," of course is a play on "rag." The music can be found on the Lester Levy Collection website: link.

The opening of the chorus (refrain) sets up an interval frame ^5-^8, both rising and falling (boxed notes).

The potential of this frame is eventually realized in the close. The chorus is not in the familiar 32-bar AABA design: it is a double period whose first unit is a sentence (see the continuation phrase in the example below -- first four bars) and whose second unit (consequent) is expanded by 4 bars -- those extra bars appear in the second example below. As the opening bar above (repeated at the end of the first example below, with ^1) shows, D5 is well defined as a focal note. Scale degree ^2 is reached at the end of the first unit, and I suppose could be called an interruption, but I have become increasingly skeptical of that term and would find neighbor note quite sufficient: so ^1 -- ^2 -- ^1.

In the consequent D5 descends by sequence down to B4 (not A4) and then rises again to C#5-D5 in the cadence.

Chorus ending:

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

Distler, "Der Gärtner," third version

Hugo Distler's Opus 19 is a large collection of a cappella songs to texts by Eduard Mörike. Several of the texts were set in multiple versions, including "Der Gärtner." I am discussing the third version, which is for three-part men's chorus. Because Distler's music is under copyright, I reproduce only the opening two measures, with an annotation, and then offer the entirety of my analysis.

The uncertainty of the tonal basis of the opening seems to dissipate by bars 4-5, with a secure cadence to Bb. Everything thereafter, however, is in F, including the close. Thus the possible Bb: ^3 at the beginning turns out to be F: ^6. Because the tonal design is reminiscent of the first strain of many small binary forms -- as Bb: I-V -- Distler succeeds in balancing the two tonalities beautifully.

Continuation of the analysis graph:

The uncertainty of the tonal basis of the opening seems to dissipate by bars 4-5, with a secure cadence to Bb. Everything thereafter, however, is in F, including the close. Thus the possible Bb: ^3 at the beginning turns out to be F: ^6. Because the tonal design is reminiscent of the first strain of many small binary forms -- as Bb: I-V -- Distler succeeds in balancing the two tonalities beautifully.

Continuation of the analysis graph:

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

Prokofiev, Classical Symphony, Gavotte

The third movement in Prokofiev's Classical Symphony (1917) is a very compact—and comically heavy-footed—gavotte with a musette trio. Here is the piano reduction of the gavotte itself only:

In this rough reduction sketch, note the inverted arch shapes, short in section A, longer and covering all of section B. The detailed harmonic analysis reflects the importance to the piece's expression of its deceptive progressions and sudden shifts.

A formal Schenker graph bases the opening on the frame ^3-^5, with ^5 appearing first and, as it turns out, remaining primary throughout. The simple ascent is complicated by the C# major displacement with a G# bass -- see the reduction above for details. Since everything is moved down a half-step (from D to C# major), what "should be" ^5 (A5) is now ^5 (G#5). Three notes are affected that way -- I've marked them with asterisks.

In this rough reduction sketch, note the inverted arch shapes, short in section A, longer and covering all of section B. The detailed harmonic analysis reflects the importance to the piece's expression of its deceptive progressions and sudden shifts.

A formal Schenker graph bases the opening on the frame ^3-^5, with ^5 appearing first and, as it turns out, remaining primary throughout. The simple ascent is complicated by the C# major displacement with a G# bass -- see the reduction above for details. Since everything is moved down a half-step (from D to C# major), what "should be" ^5 (A5) is now ^5 (G#5). Three notes are affected that way -- I've marked them with asterisks.

As the graph shows, in section B, the lower voice F# moves about neighbors. The orchestral score confirms the meandering of F# about E-E# and G -- see the circled notes in the clarinets, horns, and (at the end) second violins. A particularly pleasing detail is the "piccolo" height ^7-^8 in the flute -- boxed.

Monday, February 20, 2017

Postscript to the post on 5-6 figures

One of the examples in yesterday's post was from David Damschroder's article: the opening of Schubert's Minona, D.152 (1815). A curiosity in this melodrama's ending is worth a look here. When the protagonist finds her lover, killed by an arrow, she says/intones/sings the following:

Circled notes E5 and F5 are the focal pitches (note they are doubled in the piano in the second system).

She then quickly (plötzlich = suddenly or abruptly) pulls out the arrow and stabs herself ("stösst ihn . . . mit Hast in den Busen") -- boxed notes E5-F#5-Fnat5 -- and sinks down to die (Eb5-D5-C5 and a strongly implied B5). A closing A5 is in the piano coda. It is a bit absurd to be charting focal notes and lines across the ever-changing surface of a melodrama, but on this last page I think it is possible to hear a descent from E5 by step down to A4. a "five-line."

The piano follows the voice -- well, actually, precedes it to F#5 (circled note marked ^#6) -- and then to Fnat5, after which it holds F5, then drops to G#4 -- continued series of circled notes), also closing on A4 in the piano's coda. The simplest voice leading wouldn't follow this sequence in the uppermost notes of the right hand -- at sehr langsam Bb4 would go down to G#4 (the voice does this in the lower half of its register) and F5 would drop the octave to F4, but I think that is misleading here as the F5 is already doubled by F4 on the first beat of the bar (at "Schnee").

Circled notes E5 and F5 are the focal pitches (note they are doubled in the piano in the second system).

She then quickly (plötzlich = suddenly or abruptly) pulls out the arrow and stabs herself ("stösst ihn . . . mit Hast in den Busen") -- boxed notes E5-F#5-Fnat5 -- and sinks down to die (Eb5-D5-C5 and a strongly implied B5). A closing A5 is in the piano coda. It is a bit absurd to be charting focal notes and lines across the ever-changing surface of a melodrama, but on this last page I think it is possible to hear a descent from E5 by step down to A4. a "five-line."

The piano follows the voice -- well, actually, precedes it to F#5 (circled note marked ^#6) -- and then to Fnat5, after which it holds F5, then drops to G#4 -- continued series of circled notes), also closing on A4 in the piano's coda. The simplest voice leading wouldn't follow this sequence in the uppermost notes of the right hand -- at sehr langsam Bb4 would go down to G#4 (the voice does this in the lower half of its register) and F5 would drop the octave to F4, but I think that is misleading here as the F5 is already doubled by F4 on the first beat of the bar (at "Schnee").

Sunday, February 19, 2017

On 5-6 figures and sequences

In 2006, David Damschroder published an article on 5-6 sequences in the music of Schubert. These (though not necessarily in Schubert) would seem to be good candidates for participation in rising cadence gestures, since, in the clichéd progressions of the Italian pedagogical (partimenti) tradition, 5-6 patterns rise -- see (a) below --, whereas the complement, 6-5, falls. Here are links to some examples from partimenti rules and exercises: link; link; link.

Example (a) below is reproduced from the article, where it is example 3d. The author takes this as the prototype for a number of diatonic and—his main topic in the article—chromatic figures, including one in which the second chord is in root position rather than first inversion (see Example b, first item below; his 3e). This "thirds and fourths" pattern (or "thirds and fifths," if you drop the last bass note an octave) is ubiquitous in historical European musics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and so of course one can locate two other foundational voiceleading figures -- see the second and third examples under (b) below. The majority of Damschroder's examples from Schubert actually use these latter between upper voice and bass, and at least two of those that do maintain 5-6 between upper voice and bass have 6/4 chords (!) in the second position of the figure.

One striking example of the stricter chromatic 5-6 sequence is Damschroder's Example 9, the opening of Schubert's "Minona," D.152 (see below). This early work (1815) is by no means a Lied; it is a melodrama in the manner of those by Benda and others from the 1790s. Its stylistic foundation is the accompanied recitative, and therefore we might well expect to find a somewhat strange progression at the beginning (and elsewhere, for that matter). The introduction is a music of foreboding and strangeness -- what we hear when the singer enters is an image of darkness, storm, and fear. (Eventually, the young woman is drawn out into the night to find her lover dead at the hands of her father; she decides to take the arrow that killed him and die alongside -- more on that below. If all this seems pretty dismal, in the manner of the early Romantics, recall that early death among all urban social classes had become a serious societal problem by the end of the eighteenth century, especially from syphilis and tuberculosis. The revolution of the Romantics was to draw this sort of tragedy into the present, not keep it more emotionally distant by using ancient stories and characters.)

I have added asterisks to show the striking augmented sixth chords that are responsible for continually shifting the direction of the harmony. At ** and the arrow, Schubert breaks the pattern in order to stay on the dominant of the initial key, A minor.

Returning to the diatonic 5-6 sequence, for my purposes here, example (c) below is the one of interest. I have rewritten and extended example (a) to create an ascending cadence beginning from ^5 over I. This is an extraordinarily easy progression to generate, yet, as I have written on numerous occasions previously, the pressure of musical fashion and practice rooted in Italian models seems to have prevented its common usage. In the eighteenth century (as in the seventeenth), ascending cadence gestures -- though rarely with this progression, it must be said -- are found most often in northern dance musics and the French court music derived originally from those musics. Only near the end of the century, probably under the influence of other dance musics--the waltzing dances of Germanophone countries--did the rising line cadence gesture find its way into symphonic music (in the menuets of the late symphonies of Haydn, notably) and eventually into opera (in the 1830s and again through the importation of the by-then universally fashionable waltz and related social dances).

What is missing, most often is the second chord, vi, which of course undermines the entire notion of a repeated 5-6 pattern. Süssmayr's trio to the tenth of his 12 Menuets is typical. (I wrote about pieces in this set here: link.)

In Hummel's Six German Dances with trios, op. 16, vi is present, but any vestige of a 5-6 figure is really impossible to pull from this. I am, indeed, doubtful even about the rising line I've charted. (On the other hand, the descending 8-line in the first strain is as clear as it could possibly be.)

Example (a) below is reproduced from the article, where it is example 3d. The author takes this as the prototype for a number of diatonic and—his main topic in the article—chromatic figures, including one in which the second chord is in root position rather than first inversion (see Example b, first item below; his 3e). This "thirds and fourths" pattern (or "thirds and fifths," if you drop the last bass note an octave) is ubiquitous in historical European musics of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and so of course one can locate two other foundational voiceleading figures -- see the second and third examples under (b) below. The majority of Damschroder's examples from Schubert actually use these latter between upper voice and bass, and at least two of those that do maintain 5-6 between upper voice and bass have 6/4 chords (!) in the second position of the figure.

I have added asterisks to show the striking augmented sixth chords that are responsible for continually shifting the direction of the harmony. At ** and the arrow, Schubert breaks the pattern in order to stay on the dominant of the initial key, A minor.

Returning to the diatonic 5-6 sequence, for my purposes here, example (c) below is the one of interest. I have rewritten and extended example (a) to create an ascending cadence beginning from ^5 over I. This is an extraordinarily easy progression to generate, yet, as I have written on numerous occasions previously, the pressure of musical fashion and practice rooted in Italian models seems to have prevented its common usage. In the eighteenth century (as in the seventeenth), ascending cadence gestures -- though rarely with this progression, it must be said -- are found most often in northern dance musics and the French court music derived originally from those musics. Only near the end of the century, probably under the influence of other dance musics--the waltzing dances of Germanophone countries--did the rising line cadence gesture find its way into symphonic music (in the menuets of the late symphonies of Haydn, notably) and eventually into opera (in the 1830s and again through the importation of the by-then universally fashionable waltz and related social dances).

What is missing, most often is the second chord, vi, which of course undermines the entire notion of a repeated 5-6 pattern. Süssmayr's trio to the tenth of his 12 Menuets is typical. (I wrote about pieces in this set here: link.)

In Hummel's Six German Dances with trios, op. 16, vi is present, but any vestige of a 5-6 figure is really impossible to pull from this. I am, indeed, doubtful even about the rising line I've charted. (On the other hand, the descending 8-line in the first strain is as clear as it could possibly be.)

Reference: David Damschroder, "Schubert, Chromaticism, and the Ascending 5--6 Sequence," Journal of Music Theory 50n2 (2006): 253-275.

Saturday, February 18, 2017

Wekerlin, Der Tanz

One final entry in what I suppose might be called the "international series." Wekerlin's Der Tanz (~1875), like the Alsatian Laendler (link to that post) is a set of waltzes for piano four-hands, and here again I have supplied the prima part along with just the left hand of the secunda part.

The first strain of n1 is in the manner of a musette-style trio, not a more typical lyrical or promenade opening. The play of ^7-^6 with ^6-^5, however, is certainly characteristic. (Examples of musette or hurdy-gurdy bass passages in the Schubert dances include D145ns9 & 10, D366n3, D734n15, D790ns5 & 7.)

The first strain of n1 is in the manner of a musette-style trio, not a more typical lyrical or promenade opening. The play of ^7-^6 with ^6-^5, however, is certainly characteristic. (Examples of musette or hurdy-gurdy bass passages in the Schubert dances include D145ns9 & 10, D366n3, D734n15, D790ns5 & 7.)

Friday, February 17, 2017

Costa Nogueras, from 12 Composiciones musicales (1881), continued

In the previous post, I commented on the first three numbers in the 12 Composiciones musicales (1881) by Vicente Costa Nogueras. Today I look at the last three, a Fantasia-Impromptu (n10), a waltz "Arlequin" (n11), and a March (n12).

The Fantasia-Impromptu is a larger scale piece in a ternary form with a strongly contrasting middle section (Allegro giocoso in the outer sections, Andante Cantabile in the middle one). After a six-bar introduction, the principal theme enters in a double period in which both units end on the dominant. Here is the first:

Now this unit is repeated, finally closing the A-section in the tonic and introducing a transparent ascent from ^5 to ^8 in the cadence.

All this is repeated at the end of the piece, and a brief rousing coda follows:

The second strain (trio) of n2 leaves little doubt about its attention to ^5, and ^6 as its neighbor.

The March (n12) that closes the collection is a straighforward example of the "mirror Urlinie" from ^8 down to ^5 and then back up again in the cadence.

The Fantasia-Impromptu is a larger scale piece in a ternary form with a strongly contrasting middle section (Allegro giocoso in the outer sections, Andante Cantabile in the middle one). After a six-bar introduction, the principal theme enters in a double period in which both units end on the dominant. Here is the first:

After a contrasting middle of 19 bars, the theme returns, though now the second unit is entirely new -- but once again ends on the dominant):

Now this unit is repeated, finally closing the A-section in the tonic and introducing a transparent ascent from ^5 to ^8 in the cadence.

All this is repeated at the end of the piece, and a brief rousing coda follows:

Arlequin (n11) is a conventionally designed waltz set with a short introduction, four waltzes, and a coda that quotes the first waltz. It is unusual in the progression of keys: F-Bb-Eb-Ab and a return to F through a quick modulation in the coda.

The first strain of waltz n1 gives a prominent place to ^3 (A5) in the first unit, but the second runs a line directly from ^5 over a typical TSDT functional progression.

The second strain (trio) of n2 leaves little doubt about its attention to ^5, and ^6 as its neighbor.

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Costa Nogueras, from 12 Composiciones musicales (1881)

Recent posts on nineteenth century music have brought forward composers from the Alsace (Wekerlin), and Norway (Lehmann). Continuing the international theme, two posts will look at music by Vicente Costa Nogueras, a Spanish (Catalan) composer who lived from 1852 to 1919. He was a pianist, professor in the conservatory at Barcelona, and he wrote predominantly music for that instrument, but also works for the stage and orchestra, as well as songs. The 12 Composiciones musicales (1881) appear to be a gathering of individually published pieces. Here is the cover page, which lists them all; I have added numbers to show the ordering in the PDF file on IMSLP. Pages in the volume are not numbered consecutively.

Polichinella is n2 in the set, a polka whose melody--another double period--takes the inverted arch form and finishes with ^6-^7-^8.

The Mazurka (n3) is named Colombina (why Costa Nogueras invokes the commedia del'arte characters is unknown--we will see Harlequin too in n11). Here, the main figure is an ascent from ^5 to ^8, although in the cadence ^5 substitutes for an obviously intended ^7.

In the second strain, likewise, an ascending line is the main figure. In a formal analysis graph, I would treat this as a three-part Ursatz, with ^3/^5.

Six of the twelves pieces incorporate prominent rising lines. The opening "Melodia" is in a ternary form, where A is a double period closing on the dominant, B is a typically unstable middle section, and the reprise is rewritten -- see below. The opening presentation phrase is from the beginning, as is the first idea in the continuation. After that is a two-bar insertion in the piano, and then a considerable expansion of the cadential progression. Scale degree ^5 is quite clear at (a), as is the transposition up a step at (b), and the expressive leap at (c) -- which is magnified in the reprise by the piano's "echo" at (d). At (e) we hear the figure from (c) again but now touching and holding ^6; after a fall from that note, the line closes in the lower octave.

Polichinella is n2 in the set, a polka whose melody--another double period--takes the inverted arch form and finishes with ^6-^7-^8.

The Mazurka (n3) is named Colombina (why Costa Nogueras invokes the commedia del'arte characters is unknown--we will see Harlequin too in n11). Here, the main figure is an ascent from ^5 to ^8, although in the cadence ^5 substitutes for an obviously intended ^7.

In the second strain, likewise, an ascending line is the main figure. In a formal analysis graph, I would treat this as a three-part Ursatz, with ^3/^5.

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

From 204 Country Dances (~1775), part 3

This is the final post in the series on Straight & Skillern's collection 204 Country Dances (~1775). Today I look at three "special cases."

The two strains of "Chelsea Stage" are nearly identical, the only changes in the second being in bars 1-2 and a single note in bar 7. Although progress through the octave in the second phrase is obvious, just whether this can be resolved into a unidirectional line is not.

One possibility is shown below, in form of a "split" line where an internal ascent goes from ^1 to ^5 (beginning of the boxed notes), then a simple rising line follows to ^8. I don't find this entirely satisfying because of the sharp trajectory running toward and reaching ^9, but one can use substitution frequently found in cadences and specifically involving the dominant: ^9 substitutes for ^2 here, in the same way that, according to the traditional Schenkerian, ^7 commonly substitutes for ^2 in the descending line.

An alternative is to elevate the ^3 in the first bar of the strain, but this is decidedly less plausible. In previous posts I have observed that it is common in such small pieces as these to make an expressive "leap" above the prevailing register at the beginning of the second strain. To choose the isolated note A5 here would seriously unbalance the prevailing expressive gestures of this dance.

Finally, then, "Cave of Enchantment" is in a small ternary design with a truncated reprise and a close in the dominant for the first strain. Emphasis on ^1, ^5, and ^8 sets the frame for the first strain. The opening of the second shifts the basic idea to the dominant level, but the result is draw out the third, F#5, which is given on the first beat three times in a row before leading to G5, thus ^7-^7-^7-^8. In the reprise, then, attention is easily shifted to G5.

Thus, I would read the second strain as given below.

The two strains of "Chelsea Stage" are nearly identical, the only changes in the second being in bars 1-2 and a single note in bar 7. Although progress through the octave in the second phrase is obvious, just whether this can be resolved into a unidirectional line is not.

One possibility is shown below, in form of a "split" line where an internal ascent goes from ^1 to ^5 (beginning of the boxed notes), then a simple rising line follows to ^8. I don't find this entirely satisfying because of the sharp trajectory running toward and reaching ^9, but one can use substitution frequently found in cadences and specifically involving the dominant: ^9 substitutes for ^2 here, in the same way that, according to the traditional Schenkerian, ^7 commonly substitutes for ^2 in the descending line.

An alternative is to elevate the ^3 in the first bar of the strain, but this is decidedly less plausible. In previous posts I have observed that it is common in such small pieces as these to make an expressive "leap" above the prevailing register at the beginning of the second strain. To choose the isolated note A5 here would seriously unbalance the prevailing expressive gestures of this dance.

"Bevis Mount" is a collection unto itself -- four independent strains that bear no relation to each other beyond being complete eight-bar themes in the same key and all closing in the home key. The second strain is of interest. The close in the upper register is definite, but here again a unidirectional line seems implausible.

Finally, then, "Cave of Enchantment" is in a small ternary design with a truncated reprise and a close in the dominant for the first strain. Emphasis on ^1, ^5, and ^8 sets the frame for the first strain. The opening of the second shifts the basic idea to the dominant level, but the result is draw out the third, F#5, which is given on the first beat three times in a row before leading to G5, thus ^7-^7-^7-^8. In the reprise, then, attention is easily shifted to G5.

Thus, I would read the second strain as given below.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)