Ball's Musical Cabinet was published in two volumes. The three pieces discussed yesterday are from volume 1. From volume 2, I have chosen three more: "The Carpet Weaver," "Peggy Ban," and "The Tank." The first two of these are well-known tunes, like those in yesterday's post. About "The Tank," I know nothing more.

"The Carpet Weaver" is unusual in its boundary play, a Schenkerian term for melodic figures above the basic line. Here we would assume through the first phrase that the focal pitch is F#5, but in the second phrase of both theme statements, F#5 disappears, and attention goes entirely to the lower register, the end result being a mirror, ^8 down to ^5 and then back up again.

On the other hand, in the second half F#5 gains considerably, but the usual B-section contrast (at "vow'd") and the melodramatic long note (at deny'd him") are still not enough to displace the octave (that is, D5) as the focal note.

"Peggy Ban" (better known as "Peggy Bawn"). The play of ^3, as F#5, above the focal note ^8 is very similar to "The Carpet Weaver."

I've isolated the interval frame (which I would take to be a proto-background) in this version:

"The Tank" is a curious piece -- no song, it is highly violinistic, which character it promptly announces with the octaves in bars 1-2. I put it down to an eighteenth-century contredanse, perhaps put in by the publisher because there was empty space on the page (I have seen more obvious insertions in other collections of the period). Note that every phrase is different. Thus, each strain is what Caplin calls an antecedent + continuation hybrid. I use the term "galant theme" because this particular hybrid is especially common in virtually all types of instrumental music from roughly 1750-1800. Periods are more likely in contredanses (a fact reflected in the themes of many finales in Classical period sonatas and symphonies), so in another sense, then, "The Tank" is unusual.

The second through fourth phrases are quite distinct from the first: all have interesting—but differing—plays on ^3 and ^5 (as F#5-A5).

Sunday, March 18, 2018

Saturday, March 17, 2018

Three from Ball's Musical Cabinet

Ball's Musical Cabinet, or Compleat Pocket Library for the Flute, Flaeolet, [sic] Violin &c. was published about 1820, according to its IMSLP page: link. I have no further information about it, but the date, if broadly taken, is plausible: many such inexpensive collections of well-known dances and songs were published in the first half of the nineteenth century. The evidently poor quality of the paper suggests earlier rather than later.

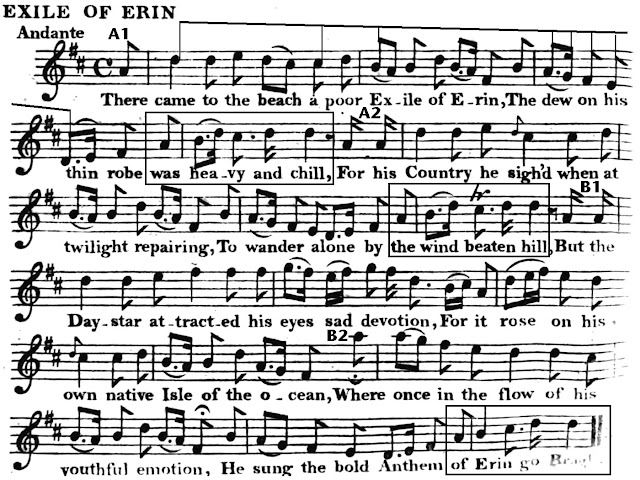

From this volume, I have extracted three dance-songs, all of which are very well-known. The "Exile of Erin" focuses on ^8, to which its figures continually return. The opening of B1 and B2 offer the "play in a register above" that one commonly finds in these subordinate form sections (not unrelated, in affective and functional terms, to the bridge in the American ballad standard). Here the repetitions of the rising cadence (boxed) carry particular weight, as their last appearance sets "Erin go Bragh."

The main theme phrase expresses a mirror figure, ^8 down to ^5, then up again:

"Kitty of Coleraine" would make an interesting study of the play of registers, but I will confine myself here to the main shapes of lines -- these are neighbor note figure about a constant ^8. In the main cadences—lines four and eight—a line returns to ^8 from below.

"Robin Adair" is a straightforward example of the case where a framing sixth, ^5 below, ^3 above, or A4-F#5 here, generates a wedge figure converging on the tonic note, here D5. I have sorted this out in the graphic below the score.

From this volume, I have extracted three dance-songs, all of which are very well-known. The "Exile of Erin" focuses on ^8, to which its figures continually return. The opening of B1 and B2 offer the "play in a register above" that one commonly finds in these subordinate form sections (not unrelated, in affective and functional terms, to the bridge in the American ballad standard). Here the repetitions of the rising cadence (boxed) carry particular weight, as their last appearance sets "Erin go Bragh."

The main theme phrase expresses a mirror figure, ^8 down to ^5, then up again:

"Kitty of Coleraine" would make an interesting study of the play of registers, but I will confine myself here to the main shapes of lines -- these are neighbor note figure about a constant ^8. In the main cadences—lines four and eight—a line returns to ^8 from below.

"Robin Adair" is a straightforward example of the case where a framing sixth, ^5 below, ^3 above, or A4-F#5 here, generates a wedge figure converging on the tonic note, here D5. I have sorted this out in the graphic below the score.

Thursday, March 15, 2018

The blog's new subtitle

Today's post is no. 250. In celebration, I have added a descriptive subtitle to the blog's banner.

[I removed it again in June but have left the post as is.]

I made the assertion contained in the subtitle in connection with the waltz ninth. The post (link) was the last (before a postscript) in the "JMT Notes" series; a post announcing an essay gathered from the series is here: link.

It is worth reproducing my comment on the waltz ninth, with its related graphic:

I hesitated before adding the subtitle insofar as it suggested that the ascending cadence gesture was proper to the nineteenth century, not other eras. That is, of course, incorrect: to date the largest number of rising lines—here defined as those easily understood as lines with focal notes, or as Urlinien—came from John Playford's English Dancing Master and the manuscript collection of contredanses compiled under the direction of Johann Bülow for the Danish court, or from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, respectively. On the other hand, the burden of numbers has been inexorably moving to the nineteenth century—virtually all new "discoveries" have been there, including a large number in the works of Chaminade. I hope to write about these as time goes on.

In addition to fitting nicely with our familiar nostrums about Romantic rebellion against eighteenth-century conventions, etc., putting the focus on the rising line in the nineteenth century aligns well with theorists' revelations about a kind of shadow tonality of hexatonic relations that arise from the exploitation of chromatic mediants.

Reference

Yust, Jason. 2015. "Voice-Leading Transformation and Generative Theories of Tonal Structure." Music Theory Online 21/4: link.

[I removed it again in June but have left the post as is.]

I made the assertion contained in the subtitle in connection with the waltz ninth. The post (link) was the last (before a postscript) in the "JMT Notes" series; a post announcing an essay gathered from the series is here: link.

It is worth reproducing my comment on the waltz ninth, with its related graphic:

"Neumeyer ([JMT] 1987) . . . considers G [as ^6 in Bb major] to be an ascending passing tone rather than an upper neighbor. According to his interpretation, the G and A at the end of m. 7 [in Beethoven, Op. 22, III] are successive notes in a single voice, even though they both are sustained as part of the dominant ninth harmony over all of mm. 5–7" (Yust 2015, n33). I have written about the "waltz ninth" many times by now. . . . Yust's criticism is the same as the one I've just made with respect to proto-backgrounds and does tend to undermine the registral variant [which I claimed as the Schenkerian solution to the background in this piece]. The waltz ninth is another matter. Nineteenth-century practice is broader--more creative and expressive--than eighteenth-century proscriptions. At (a), the ninth as neighbor note; at (b), the directly resolving ninth, a cliché in the waltz repertoire by no later than 1830. Note that the essential Schenkerian melodic note, C, is nowhere to be seen (or heard) -- in four-part writing of ninth chords, one leaves out the fifth. At (c), the figure that applies to all three "extended" chords: keep the seventh below the newly added top note in ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords. At (d), the voice leading for the rising line with waltz ninth, understood as at (e) splitting the ninth in two; the same at (f) in Schenkerian notation.

I hesitated before adding the subtitle insofar as it suggested that the ascending cadence gesture was proper to the nineteenth century, not other eras. That is, of course, incorrect: to date the largest number of rising lines—here defined as those easily understood as lines with focal notes, or as Urlinien—came from John Playford's English Dancing Master and the manuscript collection of contredanses compiled under the direction of Johann Bülow for the Danish court, or from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, respectively. On the other hand, the burden of numbers has been inexorably moving to the nineteenth century—virtually all new "discoveries" have been there, including a large number in the works of Chaminade. I hope to write about these as time goes on.

In addition to fitting nicely with our familiar nostrums about Romantic rebellion against eighteenth-century conventions, etc., putting the focus on the rising line in the nineteenth century aligns well with theorists' revelations about a kind of shadow tonality of hexatonic relations that arise from the exploitation of chromatic mediants.

Reference

Yust, Jason. 2015. "Voice-Leading Transformation and Generative Theories of Tonal Structure." Music Theory Online 21/4: link.

Sunday, March 11, 2018

Chaminade, Lolita, Caprice espagnol, Op. 54

Cécile Chaminade is remembered for solo piano music and songs, and to be sure these genres represent the majority of her published work. But she also composed orchestral music (some of it with piano), wrote a full-length ballet, and chamber music (two piano trios).

Lolita, Caprice espagnol, Op. 54, was published in 1890, three years after the ballet Callirhoë, from which Chaminade derived the Scarf Dance, the frequent recital piece for which she was long best known.

The design is ABA, a very common design for character pieces throughout the nineteenth century, and the form William Caplin calls "large ternary" to distinguish it from smaller designs, especially the one known as the rounded binary form.

In the large ternary form, B is an independent section with its own theme. That is the case here.

1-4 = introductionHere is the main theme:

5-12 = the main theme (MT), an eight-bar period with transposed consequent

13-20 = MT repeated

21-28 = contrasting middle or cadence extension (codetta)?

29-52 = 13-36; that is, MT-contrasting middle-MT

Note that with a heavy pedal, the entire passage would sit on a tonic pedal point. That makes bar 21 sound at first very much like a contrasting section. Note, however, that it is just eight bars long and it doesn't close but offers a strong lead-in to the reprise of the main theme. It is this ambivalent character that will be of most interest for interpretation.

The melodic frame of the main theme would appear to rest on ^8, as Db6, but a descent from there to ^5 isn't plausible, where the descent from ^5 is unmistakable.

The first large section, A, closes with the repetition of this sturdy descent. A mode shift to the parallel and a new theme announce B. At the end of this section, we hear a quite dramatic expanded version of the lead-in from bars 25-29.

With this, the role of this gesture would seem to be defined, but the last page of Lolita brings a surprise when this lead-in turns into a structural cadence.

The design of the coda is simple: a version of the main theme plays above A major (bVI in the main key of Db major) and then we hear another huge sweep up to the tonic note, here written as C#7 and played fff.

The final bars then hammer away at "c," a figure from the B section.

The two versions of the main cadence -- the lead-in at bars 27-29 and the structural close at 120-124 -- have the same basis, shown in the figures below. The Ab5 at the beginning of each represents the ^5 from the main theme. The asterisks in the lower figure are to point out the double function (S in the first case, T in the second) for the A major chord.

Thursday, March 8, 2018

On the Beach: Ernest Gold's "Waltzing Matilda"

I have written a post for our Hearing the Movies blog in which I discuss the film On the Beach (1959): link. Ernest Gold (best known for his music for Exodus) composed the underscore, and the familiar song "Waltzing Matilda" plays a prominent part (the film is set in Australia). In the post, I comment on four instances where the ending rises rather than falls. Gold makes very striking dramatic use of this alternate ending in the film's final moments.

The point of interest here is how easily the change in the melody is made and how natural it sounds.

The point of interest here is how easily the change in the melody is made and how natural it sounds.

Saturday, March 3, 2018

Glinka, Mazurka in F major (1833-34)

The second strain of this mazurka is a transposed variant of the first strain. Both are framed by a simple ascending Urlinie from ^5 to ^8. The internal elaboration in the first phrase of each strain is a neighbor note figure that brings considerable expressive emphasis to ^6, presaging its essential role in the cadence. The overall treatment of ^6, then, is very close to Schubert's in D779n13 (link).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)