In the introduction to this minor-key series (

link), I wrote the following:

At the end of the series, I will add posts with a couple additional counter-examples (from Beethoven and Offenbach) and other posts with historical context about the Dorian octave, the examples coming mainly from Praetorius and Eyck.

Beethoven was here recently (

link), but not Offenbach: when I wrote the introduction, I anticipated finding something in

Orpheus in the Underworld, but even there Offenbach wrote in the major key! In this appendix on rising figures and the modal octave, the example list does include Praetorius and Eyck, but also Morley, Walther, and La Guerre, as well as a dance from Playford.

The Dorian and once-transposed Aeolian modes are an interesting case in point for the complex history of modes, scales, harmony, and keys in the 17th century. We'll start with the simplest examples: characteristic, conservative treatments of each.

Among the earliest posts on this blog (from 2014) is a series on rising lines in music by Jacob van Eyck, from the

Fluyten Lusthof. Here is one paragraph from the introductory post (

link).

As is well-known, in the 1640s the Dutch flutist Jacob van Eyck published a pair of remarkable volumes called Der Fluyten Lust-hof: vol Psalmen, Paduanen, Allemanden, Couranten, Balletten, Airs, &c. Konstigh en lieslyk gefigureert, met veel veranderingen. As the subtitle announces, the pieces -- all for solo flute (or solo treble instrument) -- range from Calvinist psalm tunes and well known chorales (such as Vater unser in Himmelreich) to dances and popular tunes. All of them are dressed with "divisions" (diminutions, or the technique that "breaks" a long note into smaller notes), most with multiple versions (met veel veranderingen).

In van Eyck's setting of an old tune, "Wel jan wat drommel" (which is discussed in the introductory post linked to above), we can see a firm maintenance of the Dorian scale, except for leading-tone inflections for the cadence to A in the first section and for the cadence to D in the second section. At "x" we might expect a player to lower the B to Bb, but at "y" the B makes sense as is. In fact, the expressive contrast between Bb at "x" and B nearby at "y" would by no means be out of place in this era (as we'll see in some subsequent examples). At "z1" and "z2", B is a given because the leading tone G# has already been heard. In the second section, "m" and "n" are appropriately B, as the entire passage sits in the upper tetrachord and the leading tone is heard no less than four times.

"Modo 2" indicates the first of two variations. The "gebroken" version of "x" still suggests a possible Bb and the contrast between a flat for the downward line from C5 to G4 and a natural for the upward line from G4 back to C5. At "z1", it seems unlikely that Bb would sound given the proximity to the leading tone and cadence on A (see "z2"). At "m" and "n" the same constraints that dictated B rather than Bb throughout in the theme continue to apply to the diminutions.

In "Modo 3," the second variation, the diminutions come down to mostly eighth notes. At "m" Bb seems much more likely now, to avoid a tritone leap from F4 to B4 -- and of course suggests that van Eyck may have assumed a player would use Bb at this point in the theme and first variation as well. At "n" again, B is clearly meant throughout, first because of the focus on C5, then in figures that follow from the leading tone G#. At "o" it's hard to know what to make of the two notated tritones (at "p" the tritone G-C# is heard again). Unless we want to invoke possible misprints, the first B could be done as Bb, but all others at "o", "p", and "q" are B-naturals.

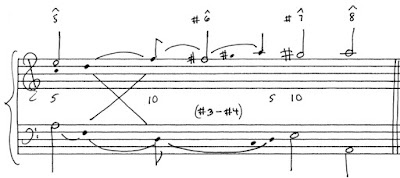

The figure below traces the diminutions in the closing cadences of Modo 2 & 3 back to the theme. The asterisks show the clichéd escape tone figure, where D-C# is embellished by an upper E. In the box, the escape tone even receives its own elaboration. These are excellent early examples of what be called the mirror to the leading-tone third: the not uncommon case where ^2 embellishes a more basic ^#7.

Van Eyck, Courante. I have written about this piece here:

link. What might seem a subtle difference in the present day was assuredly not in much of the 17th century. This courante is in "D minor" (key signature of one flat), but properly in once-transposed Aeolian mode (the mode on A transposed up a fourth or down a fifth). The presence of Bb gives the scale a different color than the Dorian -- in any case, historically, the Aeolian mode was associated with the Phrygian, not the Dorian. The Bb is carefully maintained in the courante and its two variations, with the exception of the end of variation 2 ("Modo 3"), where the turn of the cadence up toward ^8 would surely change the notated Bb to B-natural in performance.

Next, the beginning and end (untexted) of Thomas Morley's madrigal "Leave, alas! This tormenting" (1595) are given below. Notation for viols is by Albert Folop and is available on

IMSLP. I show the opening to demonstrate that it is clearly twice-transposed Aeolian (up two fourths produces a key signature of two flats). Several expressive Eb's emphasize the mode's characteristic sound, and the voice entries are in the expected positions (on D and G; not G and C, as would be the case if this were twice-transposed Dorian).

The madrigal is 88 bars long. The Aeolian octave is strictly maintained throughout, with just these two exceptions (before the end): two measures for a cadence on D (mm. 30-32 b1) and the first statement of the closing cadence below (at mm. 53-61).

The latter and its twin (mm. 79-88) at the end of the piece are indistinguishable from the Dorian because of the repetition of a rising figure (in boxes) that requires E-natural. The structural upper voice in the cadence, also using this line, makes the adjustments we would expect for an Aeolian cadence.