Note number 28 is the first in my article "The Ascending Urlinie" (Journal of Music Theory 1987) to contain a list of additional examples. In the article I wrote that motivic foregrounding and layering did not necessarily generate rising background lines. Here is my text for the first example:

n28: The Menuet of Haydn’s Symphony no. 100 is a case in point. In the first period (measures 1-8, which stand for the whole), the initial motion is strongly downward, but the final cadence produces a clear ascent from ^5 to ^8 in the upper-most part.

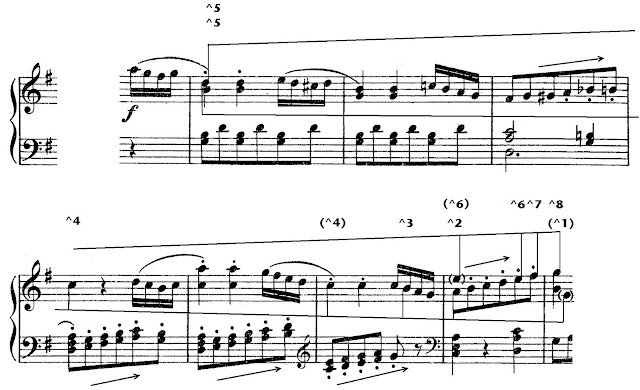

Thinking of this in Schenkerian terms—as I was in 1987—the rising line is not workable in the theme's first presentation because it doesn't mesh well with the bass, especially in bars 5-6, where one would have to imagine a doubling of bass and soprano, never a good idea. It's much easier to build a line in this way: D5 initiates a fifth-line; to C in bar 4, recapture C in bar 6, B on the last beat of that bar, then A in bar 7, and an implied G in bar 8. The ascending scale in the cadence is boundary play. See this version here:

In the reprise, on the other hand, the chromatic passing tone D# in the bass (from m. 6) is gone, and a string of diatonic figures, all rising, take over the lower parts, directly linking the chromatic scale fragment to the diatonic scale fragment (see the arrows in the figure below). As a result, the rising line from ^5 to ^8 has a clear path and pitch design can be read as well-matched to the important aspects of expression.

The text above comes from my essay Ascending Cadence Gestures: A Historical Survey from the 16th to the Early 19th Century, published on Texas Scholar Works: link.

Subsequent posts will offer more discussion of pieces named in note 28.