Chaminade, Piéce Romantique, Op. 9n1 (1880). The design is ABA, where A is a 16-bar theme closing on V rather than I--see below-- and is then repeated, B is briefly contrasting but turns out to be an 8-bar transition, and A is an altered reprise of the theme with a close on the tonic.

Here is the altered reprise.

Thursday, November 29, 2018

Thursday, November 22, 2018

Chaminade, Berceuse, Op.6

Chaminade, Berceuse, Op.6 (published c. 1878). The main theme, section A, is a 24-bar double period (12 bars each in the antecedent and consequent). Here is the consequent. The upper note Bb5 reached to begin the second 6-bar phrase might be taken as a focal note.

Section B ends with a partial return -- beginning in the third bar below. Note that the flourish has now been extended upward to Eb6.

Section C is in D major (= Ebb major). A full reprise follows, where only the latter part of the consequent is altered, as below. Here Eb6 has become Eb7 in the flourish, and the figure is now an arpeggio rather than a scale. In the eighth bar of the excerpt, the harmony A 6/5 pulls the close in a different direction. The trills maintain the register of the previous closes: so A-natural4, G-natural4, Ab4, Gb4. Above that, E-natural5, ornamented at first, turns into a sustained half-note, then F5, then Gb to close--suggesting that the prominent Gb5 from the main theme may be the best choice if one is looking for a focal tone overall.

Section B ends with a partial return -- beginning in the third bar below. Note that the flourish has now been extended upward to Eb6.

Section C is in D major (= Ebb major). A full reprise follows, where only the latter part of the consequent is altered, as below. Here Eb6 has become Eb7 in the flourish, and the figure is now an arpeggio rather than a scale. In the eighth bar of the excerpt, the harmony A 6/5 pulls the close in a different direction. The trills maintain the register of the previous closes: so A-natural4, G-natural4, Ab4, Gb4. Above that, E-natural5, ornamented at first, turns into a sustained half-note, then F5, then Gb to close--suggesting that the prominent Gb5 from the main theme may be the best choice if one is looking for a focal tone overall.

Thursday, November 15, 2018

Chaminade, Mazurka, Op. 1n2

Cécile Chaminade, Mazurka, Op. 1n2 (1869). In the multi-strain with reprise design typical of 19th century dances, here as ABACDCAEA, where C, D, and E are in the subdominant. The A strain is shown below. Using Schenker terms and following one of my 1987 articles, I would call this a three-part Ursatz, with soprano descant (^3-^4-^4-^3) and alto Urlinie ^5-^6-^7-^8. Bars 5-8 repeat 1-4.

Reference: Neumeyer, David. "The Three-Part Ursatz." In Theory Only 10/1-2: 3-29.

Reference: Neumeyer, David. "The Three-Part Ursatz." In Theory Only 10/1-2: 3-29.

Wednesday, November 14, 2018

Schenkerian analysis guide published

Not entirely germane to this blog, as the Guide is very traditional pedagogy, but I will nevertheless announce a compact online version of A Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, originally published in 1992. Susan E. Tepping was my co-author. It is available on the Texas Scholarworks platform: link.

Here is the abstract:

This essay is an introduction to Schenkerian analysis, one model for linear analysis/interpretation of music. This condensed version of an out-of-print manual, co-authored with Susan Tepping, provides the basis of an efficient learning experience and includes only the material from the original book necessary to that end. Two supplementary files contain appendices (File 2) and text and figures from the original book deleted from this file (File 3).

Here is the abstract:

This essay is an introduction to Schenkerian analysis, one model for linear analysis/interpretation of music. This condensed version of an out-of-print manual, co-authored with Susan Tepping, provides the basis of an efficient learning experience and includes only the material from the original book necessary to that end. Two supplementary files contain appendices (File 2) and text and figures from the original book deleted from this file (File 3).

Update 18 December 2024: I have published A Guide to Schenkerian Analysis, Early 20th Century. Here is the link.

Thursday, November 8, 2018

Shaw's Musical Olio (1814)

An interesting item found on IMSLP: Oliver Shaw (1779-1848), Musical Olio. Comprising a selection of valuable Songs, Duetts, Waltzes, Glees, Military Airs, &c. &c. adapted to the Piano-Forte, with an accompaniment for the Flute or Violin. Selected and published in numbers, by Oliver Shaw. Providence: H. Mann & Co. Of these, four issues are available on IMSLP: March, June, September, and December 1814. The pieces are consecutively numbered. Five of them are presented below.

The term "olio" may seem odd-to-humorous today, but it was a common 19th and even early 20th century term for miscellaneous incidental pieces intended for vaudeville, minstrel shows, and similar kinds of entertainments. More generally it meant "miscellany" or "hodge-podge" (link to dictionary definition). (An internet search will show that "olio" is still very much alive, in periodicals with the older sense of miscellanies, in a food-sharing app, the Anglicized version of the Spanish dish olia, a Los Angeles based rock group, etc.)

9_contentment. The figure is in the 1st voice and might be read as an incomplete mirror, where ^8 drops directly to ^5 (bars 3-4), then returns by line (bars 5-8) -- or as a double neighbor figure about ^8.

17_Belles. A 6/8 country dance that might well have been called a reel. Complicated though this might seem, I hear a principal voice rising from ^1 to ^3 (bars 1-2, again in 5-6 and 13-14), answered by ^6-^7-^8 in the same part in bars 3-4 but in the "discant" in bars 7-8 and 15-16.

19_Himmel waltz. Dance and trio (at the dolce), with the rising figure in the former.

39_Moore. Music repeated for a second verse. Small ternary form in the verse. From ^9 to ^8 in the voice's opening (bar 5), then focus on figures in the tetrachord, ^5-^8.

49_Cottage dance. A simple 2/4 contradance, the music (not the suggested figures) having some of the character of a schottish. Equally simple in design: mirror Urlinie in the first strain, same but leading on the dominant in the second strain. Ends with reprise of the first strain.

The term "olio" may seem odd-to-humorous today, but it was a common 19th and even early 20th century term for miscellaneous incidental pieces intended for vaudeville, minstrel shows, and similar kinds of entertainments. More generally it meant "miscellany" or "hodge-podge" (link to dictionary definition). (An internet search will show that "olio" is still very much alive, in periodicals with the older sense of miscellanies, in a food-sharing app, the Anglicized version of the Spanish dish olia, a Los Angeles based rock group, etc.)

9_contentment. The figure is in the 1st voice and might be read as an incomplete mirror, where ^8 drops directly to ^5 (bars 3-4), then returns by line (bars 5-8) -- or as a double neighbor figure about ^8.

17_Belles. A 6/8 country dance that might well have been called a reel. Complicated though this might seem, I hear a principal voice rising from ^1 to ^3 (bars 1-2, again in 5-6 and 13-14), answered by ^6-^7-^8 in the same part in bars 3-4 but in the "discant" in bars 7-8 and 15-16.

19_Himmel waltz. Dance and trio (at the dolce), with the rising figure in the former.

39_Moore. Music repeated for a second verse. Small ternary form in the verse. From ^9 to ^8 in the voice's opening (bar 5), then focus on figures in the tetrachord, ^5-^8.

49_Cottage dance. A simple 2/4 contradance, the music (not the suggested figures) having some of the character of a schottish. Equally simple in design: mirror Urlinie in the first strain, same but leading on the dominant in the second strain. Ends with reprise of the first strain.

Thursday, November 1, 2018

Rounds and canons, part 2

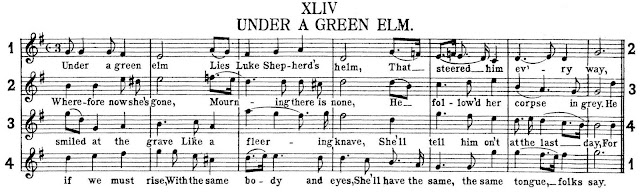

Today's examples come from volume 22 of The Works of Henry Purcell (London: Novello, 1922). The volume gathers rounds and catches (which were edited by W. Barclay Squire), as well as two and three part songs. For the rounds and catches, n = 57. The editor mentions ten other catches in Purcell's stage works (iii). Of the 57 in volume 22, six are of interest for rising figures. I discuss them below in their numerical order, not topically, though as it happens they are all closely related in design, with a well-confirmed focal tone ^8 and return to it in the cadence.

As the editor of volume 22 notes, with implicit apology, "The work [of gathering these pieces] has been rendered more troublesome owing to the fact that in many cases the original words are so grossly indecent that later editors have reprinted the music with new words, but without indicating what was their original form" (iii). The solution: "it has been thought best in the present edition either to alter the original words as little as possible or to write entirely new words, but retaining the opening phrase of the originals and inserting some play on the words, such as always distinguishes the catch from the round or canon; which course has been pursued is indicated in the notes." The singing of rounds and catches was part of men's entertainment, and the topics are largely confined to drinking, politics, and varying but often misogynistic views of women. Acknowledging all this—and also admitting that I did not include 2 or 3 pieces that would have been appropriate otherwise but whose texts, even as editorially curated, were still too offensive—here are the six.

1. Ascending figure in the third voice.

2. Wedge figure with the lower voice 1 coming up to ^8 while the upper voice 2 descends from a strong focal note ^3, A5 (as written).

3. Unusual minor key; not ascending cadence figure in voice 3 but return to a focal note ^8 (as G5, written).

4. As in no. 37, a minor key with ^8 as focal tone, but now G5 is traded between voices: bar 2 in voice 1, bar 3 in voice 3, and bars 4-5 in the voice 2.

5. Still another minor key, with the design very like no. 42.

6. If anything, the status of the focal tone ^8 is even stronger in this, with that note beginning voice 3, reached in voice 4 in bar 2, double neighbor figure in voice 3, bars 3-5, and cadence in voice 4, bars 5-7.

As the editor of volume 22 notes, with implicit apology, "The work [of gathering these pieces] has been rendered more troublesome owing to the fact that in many cases the original words are so grossly indecent that later editors have reprinted the music with new words, but without indicating what was their original form" (iii). The solution: "it has been thought best in the present edition either to alter the original words as little as possible or to write entirely new words, but retaining the opening phrase of the originals and inserting some play on the words, such as always distinguishes the catch from the round or canon; which course has been pursued is indicated in the notes." The singing of rounds and catches was part of men's entertainment, and the topics are largely confined to drinking, politics, and varying but often misogynistic views of women. Acknowledging all this—and also admitting that I did not include 2 or 3 pieces that would have been appropriate otherwise but whose texts, even as editorially curated, were still too offensive—here are the six.

1. Ascending figure in the third voice.

2. Wedge figure with the lower voice 1 coming up to ^8 while the upper voice 2 descends from a strong focal note ^3, A5 (as written).

3. Unusual minor key; not ascending cadence figure in voice 3 but return to a focal note ^8 (as G5, written).

4. As in no. 37, a minor key with ^8 as focal tone, but now G5 is traded between voices: bar 2 in voice 1, bar 3 in voice 3, and bars 4-5 in the voice 2.

5. Still another minor key, with the design very like no. 42.

6. If anything, the status of the focal tone ^8 is even stronger in this, with that note beginning voice 3, reached in voice 4 in bar 2, double neighbor figure in voice 3, bars 3-5, and cadence in voice 4, bars 5-7.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)