This post continues the topic from an earlier one, in which I wrote about n4 in Mozart's Menuets, K. 164:

link. I recently published an essay on formal functions in the first strains of menuets from Mozart to Schubert

(link to the essay) and along the way noticed ascending gestures in several pieces. Here I will write about some of Mozart's late menuets, those composed between 1788 and 1791. The pieces are K 568ns2 & 11, K 585ns1 & 3, K 599n4, and K601n1.

The 12 Menuets, K. 568n2. It's clear that the primary interval in the melody is the third F5-A5—see the first violins, horns, and oboes in the pickup and first beat of bar 1. The violins trace this interval again in bar 3 before moving decisively by step to G5. The consequent starts over, but the curious thing is that the violins completely abandon this lower third of the triad for the upper one, A5-C6 in bars 7 & 8 (boxed and marked "c"). --- I've traced the

proto-background F5-A5 (as ^1-^3) a different way: starting at "a" with the horns in bar 1 follow the circles and arrows from horns to violins to oboes to horns again. Notice that the rising line in oboe 1 and bassoon 1--boxed at "b"--is an accompanying line in the cadence. We will see Mozart introduce figures like this in subsequent examples.

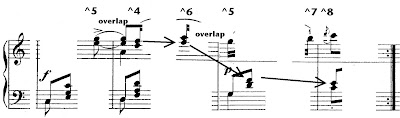

Here is the proto-background and its transformation, which I call INV (for inversion), isolated in the oboes and horns at beginning and end.

In the same set, n11, despite a decidedly angular melodic line in the antecedent phrase and a strongly contrasting second phrase, is squarely settled on scale degree ^3: B4 in the first phrase, B5 in the second phrase. In bar 7 that B5 turns from G: ^3 into D: ^6 and moves plainly up the scale in flute 1 and bassoon 1 while tracing the same path in the first violins but with register shift. I have argued in the past for this move from ^6 *down* to ^7 as a legitimate variant of the rising line but have occasionally worried about it, too. In instance, there is no doubt whatever about the origin of the first violins' figure in the voice leading of the flutes and bassoons.

In the first of 12 Menuets, K585, the first violins send a rocket figure through and past the presentation phrase, eventually going one-too-far to B5 (^6) over the subdominant, then settling back to ^5. In the cadence, the violins drop an octave and trace a line up in the sixteenth notes. In this instance again, the flutes move against the violins, but down: ^6-^5-^4-(^3), the last being what I call a hanging third or implicit third: we certainly *ought* to hear it given the shapes that precede bar 8.

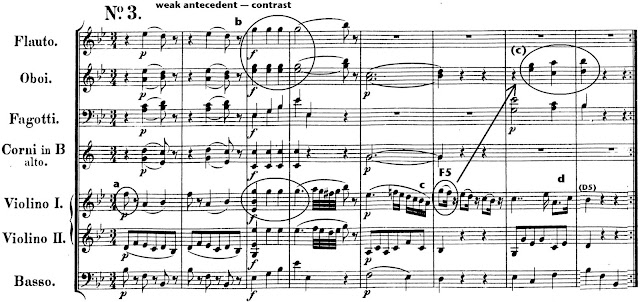

In the same set, n3 finally brings the scalewise ascent in the cadence to the uppermost register. A firm ^5 as F5--at "a"--moves up a step in the contrasting idea, circled at "b," is recovered at "c" (bar 6), and moves upward in the first oboe (doubled in the second bassoon). Against the oboe, the first violins at "d" produce another hanging third as C5 moves directly to Bb4 while Eb5 produces a lingering hint of D5.